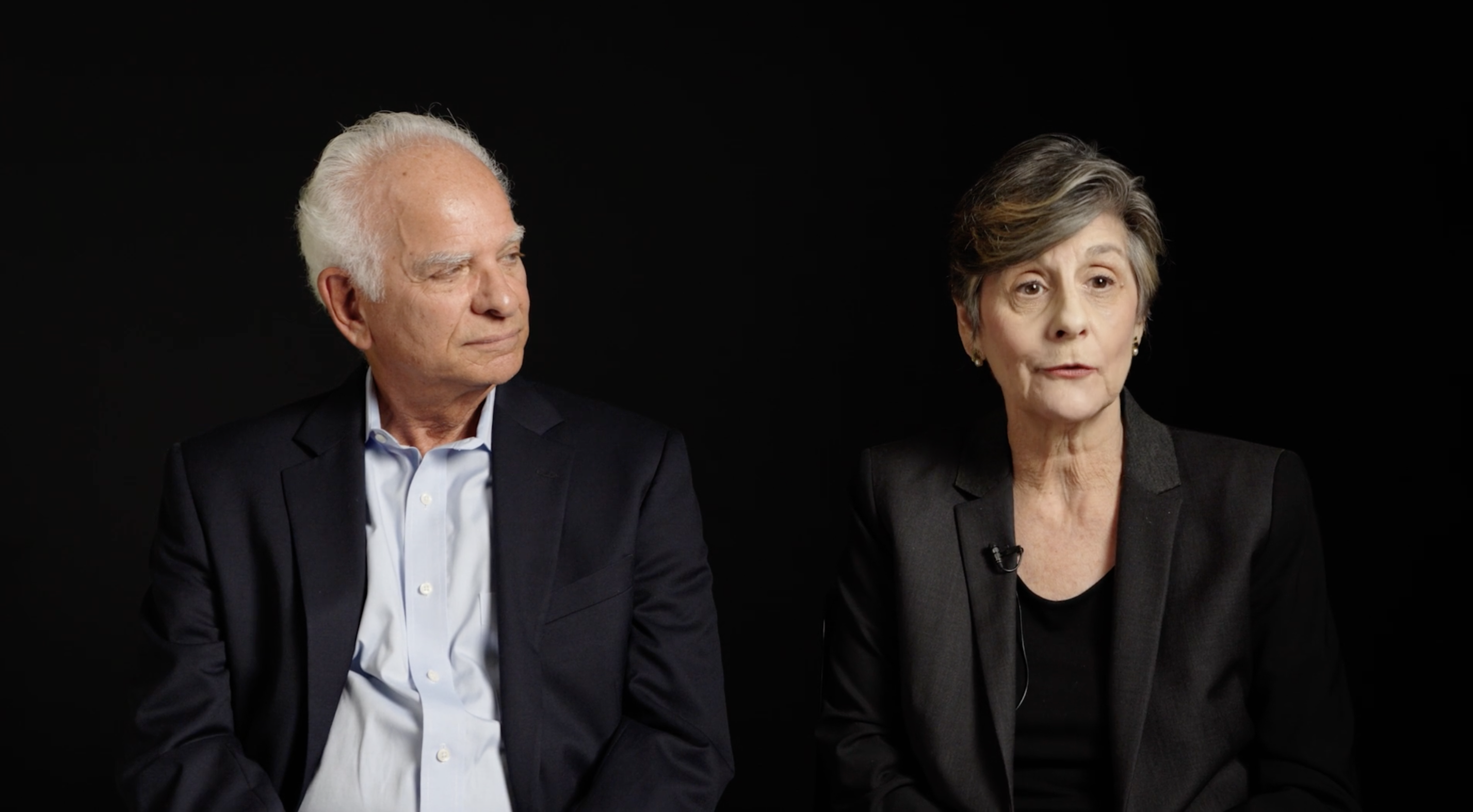

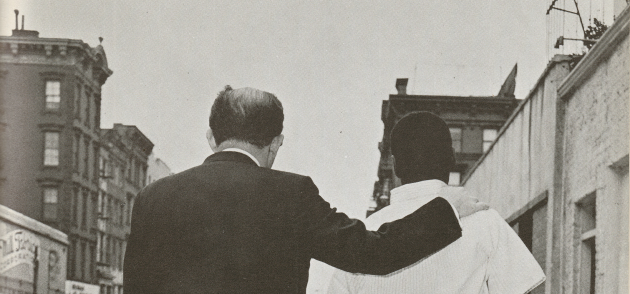

Over the course of the latter half of the 20th century, the mental health field as a whole—including providers such as the Jewish Board—gradually evolved their approaches to residential treatment for both children and adults by increasing their capacity to serve clients with the most significant needs and by relocating services closer to clients’ communities. The Jewish Board first provided residential treatment to children, mostly at its expansive Hawthorne Cedar Knolls campus in Westchester County. By the early 1980s, Jewish Board staff noted that their young residential clients had far more extensive mental health needs than the current clinical capacity at sites such as Hawthorne. To address this, Jewish Board CEO Jerome Goldsmith worked with Ilene Margolin, then Executive Director of the New York State Council on Children and Families, to develop New York State’s Residential Treatment Facilities (RTF) legislation. Margolin explained that this legislation, “created a new level of care, sort of like a step down from a psychiatric hospital, which then had clinical staff, psychiatry, etc. So that became, in that day, a more appropriate level of care for the youngsters who they [The Jewish Board] were trying to serve.”

More broadly, a federal push for “community mental health” led to the shift of funding for residential treatment from institutions run by the state to those run by not-for-profit organizations. A scathing 1972 exposé of Staten Island’s Willowbrook State School for children with intellectual disabilities only accelerated this trend towards “deinstitutionalization,” which encompassed changes in the location, size, and management of such institutions. Smaller institutions closer to clients’ home communities, administered by local not-for-profits, were intended to provide more humane and effective treatment. This process of “deinstitutionalization” often took place without sufficient attention to the particular needs of clients, without sufficient funding to support the new model, and without adequate regulation of the institutions that arose to fulfill the ongoing need for residential care. Nevertheless, Bruce Feig, former Executive Deputy Commissioner for the State Office of Mental Health reflected that, in his opinion the current system is a vast improvement over the old, but “we haven’t gotten to the next generational change, which is to make it person-centered.”

Throughout this shift, The Jewish Board continued to increase the capacities of its residential care for children through provisions of the RTF legislation, and it gradually began providing longer-term residential care for adults with mental illness as well as clients with developmental disabilities. In 1981, the state decertified several privately run foster-care agencies in Brooklyn—including a Jewish facility called Mishkon B’nai Yisroel—due to deficiencies in the care provided. The state asked The Jewish Board to take over the Mishkon facility and transition it from the foster-care system to the then “Office of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disability.” According to Jewish Board General Counsel Ellen Josem, “there was a real need for the service delivery to this population to be professionalized,” and this marked the agency’s entry into providing long-term residential care for both children and adults with developmental disabilities.

The Jewish Board’s long legacy of providing shorter-term residential care for children outside of the large Hawthorne Cedar-Knolls campus continued to provide shorter-term residential care for children with various socioeconomic and mental health needs until 2018, when the need to develop more appropriate models of care as well as conflict with the local community finally compelled its closure and replacement with a smaller, more “community based” facility in the Bronx (see “Race and Racism” Issue). The closure of Hawthorne signaled the end of over a century of Jewish Board’s residential services located beyond the city, and the transformation of all such services into a “community based” model.