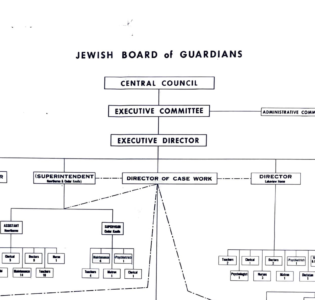

Under Dr. John Slawson’s leadership, the Jewish Board of Guardians adopted a sophisticated clinical model that integrated psychoanalysis, interdepartmental collaboration, and evidence-based mental health interventions, setting a new standard for the agency’s child guidance services.

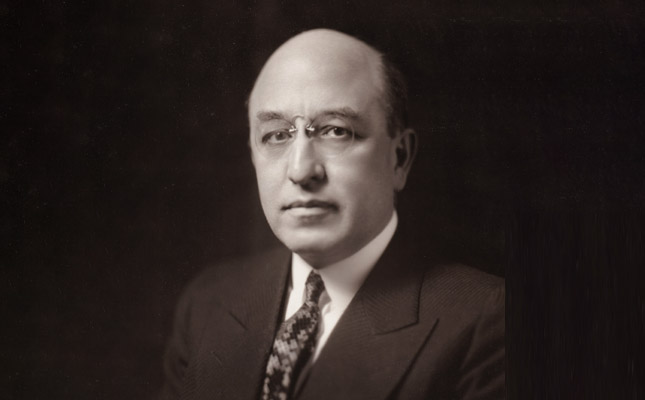

Executive Director, Jewish Board of Guardians (1932-1943)

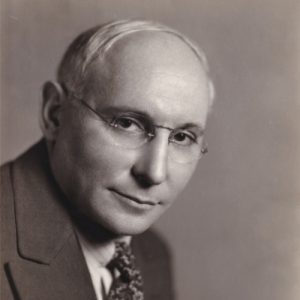

John Slawson, PhD was born in 1896 in Poltava, a city in then-Russian-ruled Ukraine. With his parents and his older brother (and Jewish Board of Guardians colleague) Samuel Richard Slavson, he emigrated to New York City in 1903. Though the two brothers settled on different English spellings for their last names, they shared a lifelong commitment to social justice.

An academically gifted student, Slawson obtained his bachelors, master’s and doctorate degrees in social psychology from Columbia University, graduating in 1927. Concurrent with his graduate education, from 1920-1924, he worked as an investigator and psychologist for the New York State Department of Welfare. His 1926 book The Delinquent Boy became a reference manual for others working in the field of child guidance and reflected his early interest in juvenile delinquency. He then went on to spend nearly a decade overseeing Jewish welfare federations in Cleveland and Detroit, before returning to New York City and accepting the position of Executive Director of the Jewish Board of Guardians in 1932.

Advancing a Sophisticated Clinical Model

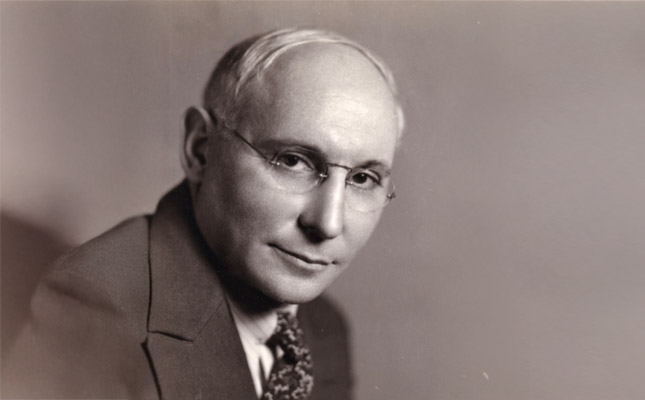

During his twelve-year tenure at the Jewish Board of Guardians, Slawson had a profound impact on the agency’s approach to mental health treatment for children. With the full support of JBG president George Zerdin Medalie, Slawson successfully advocated for the incorporation of psychiatric casework, a specialized form of social work that integrates mental health knowledge and therapeutic techniques to assess, support, and address the psychosocial needs of individuals with mental health challenges. Drawing on clinical observations, psychoanalytic concepts, and treatment-related statistics which the agency had formally begun collecting in 1930, Slawson came to believe that family stress and the home environment were playing a significant role in the experience and behaviors of the children they treated. In response to these findings, he embraced the idea that psychiatry and psychoanalysis were essential tools for child mental health treatment, as they already had been recognized to be in the treatment of adults.

Slawson also advanced the view that psychiatric social workers, given proper professional training and supervision, should be granted the authority to lead groups and do direct therapeutic work. Until this point, social workers were only allowed to play a supporting role in these realms, working under the watchful supervision of staff psychiatrists. And he worked to increase collaboration and information sharing across programs and departments, including group therapy, social work, psychiatry, research, and administration. He and other agency leaders viewed this coordinated approach as necessary for efficient and effective treatment under the integrated model, since there would be more individuals involved in each case the agency saw. Slawson was instrumental in the Jewish Board of Guardians’ move towards making diagnosis a requirement as part of evaluation and treatment.

Another major clinical intervention Slawson developed at the Jewish Board of Guardians was the idea of the ‘conditioned environment.’ This meant clinicians might be able to better address the individual needs of children within a group setting if they could observe and guide them in specific interpersonal contexts. In the mid-late 1930s, the Jewish Board of Guardians expanded its recreational activities, the enhancement of the athletic program, and the development of group theater and creative activities accordingly.

A Visionary in the Fight Against Antisemitism

As JBG executive director until 1943, Slawson was also charged with the task of running this organization at a most difficult turning point for Jews in the world, one that evolved from a time of great uncertainty and fear to war and genocide. In the 1930s, he collaborated with other relief agencies to support Jewish immigrants, helping them integrate into American society while preserving their cultural heritage. Before and during the war years, Dr. Slawson had also become deeply invested in the work of intergroup relations, and was driven by a deep desire to understand and combat antisemitism at home and abroad.

Slawson developed a close relationship during this time with a well-known and influential group of German-Jewish social scientists who today are considered the “Frankfurt School,” including Eric Fromm, Max Horkeimer, and Theodor Adorno. He invited these scholars to come together to produce a scientific study exploring prejudice, the authoritarian personality, and potential antidotes to human violence. This collaborative scholarship had a far-reaching impact, culminating with the five-volume “Studies in Prejudice” (1949). Anonymized clinical observations from both local private practice work in New York City, as well as a small number of Jewish Board of Guardians cases with adult clients, helped to inform the theories and arguments included in the collaborative study.

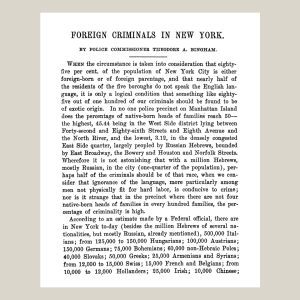

He also made important observations about the role of the Jewish Board of Guardians at the level of society and intergroup relations. In a 1981 oral history interview, Slawson noted that Hawthorne Cedar Knolls, and soon thereafter the Jewish Board of Guardians, had been founded in response specifically to false claims made highly public by New York City Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham (1906-1909) that half of delinquents in New York City were Jews. For Dr. Slawson, JBG was explicitly created not only to help immigrant children and families, but to undermine the credibility of antisemitic claims such as Commissioner Bingham’s to safeguard Jews as a group more broadly from persecution and dehumanization. The agency contributed to a broader movement during the 1940s to keep antisemitism at bay in the United States, even as the Nazis and their collaborators systematically destroyed European Jewry.

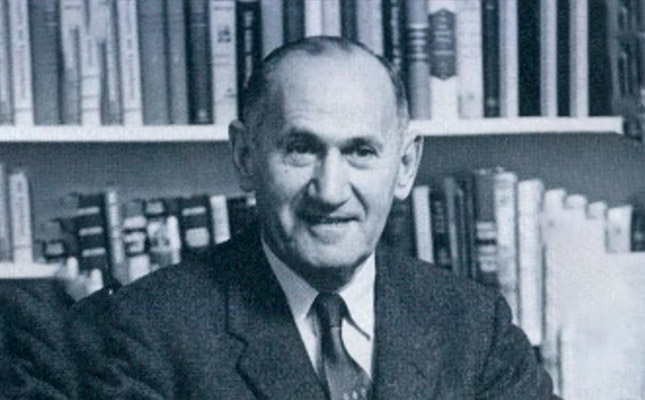

1943, Slawson left the Jewish Board of Guardians to become executive vice-president of the American Jewish Committee (AJC), where he remained until his retirement in 1967. He made the decision to join the AJC, a prominent Jewish civil rights and advocacy organization, because he felt that at that time that “the most single important thing for Jews throughout the world was what we call now the Holocaust, and to do everything possible to avoid it happening again.”

Legacy

Throughout his career, Slawson was also very active in civic and philanthropic work, including with the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies. He taught many community relations and social welfare courses, including at Hunter College in New York, the University of Michigan, and the New School for Social Research. He also served as a consultant to the White House Conference on Children and Youth, was a consultant on delinquency to the United States Children’s Bureau and the Social Security Board, and served as president of the National Conference of Jewish Communal Services. Slawson was also founder of the American Jewish Committee’s Institute of Human Relations and was part of a delegation that met in 1957 with Pope Pius XII – the first Jewish organization ever to be granted an invitation to the Vatican.

John Slawson died in 1989, but his legacy and quest to understand and subvert the forces of authoritarianism and prejudice at the social and psychological level provided a blueprint for subsequent generations of social scientists and human rights defenders to tackle these issues.

Reference List, Bibliography and Research Resources

- Celebrating a Century of Caring

- The Pioneers of Adolescent Group Psychotherapy