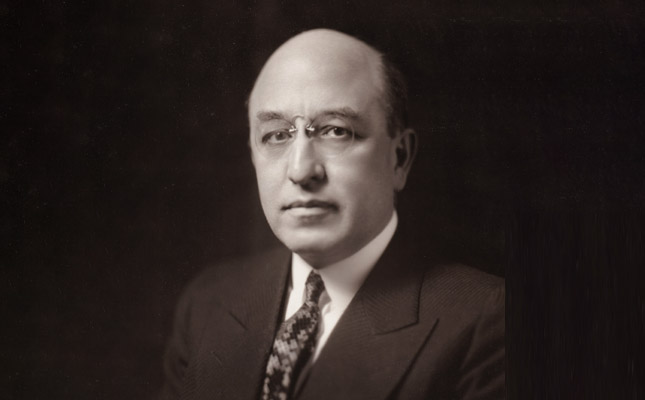

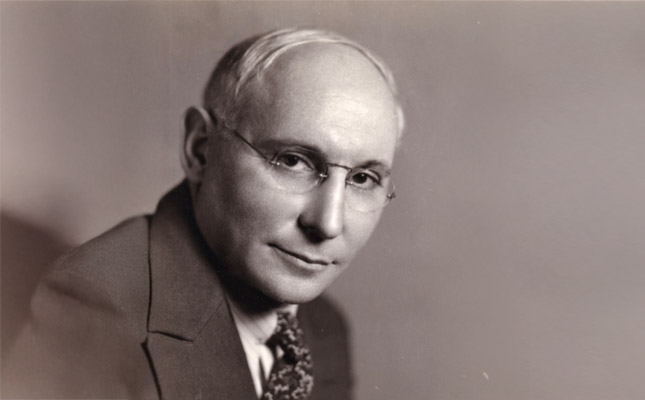

Herschel Alt was a visionary leader who transformed the Jewish Board of Guardians’ approach to child guidance and residential care, advocating for high quality and innovative treatment methods based on empathy and understanding, collaboration across systems, and the development of tools to measure treatment outcomes for troubled youth.

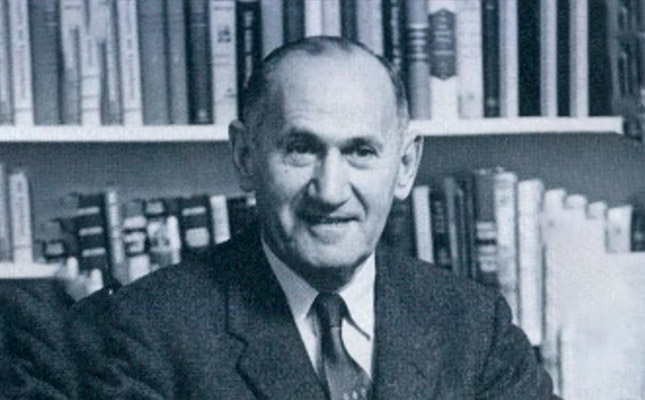

Executive Director, Jewish Board of Guardians, 1943-1965

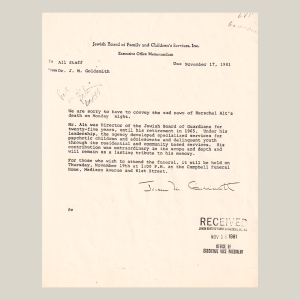

Herschel Alt (1897-1980) served as the longest-standing Executive Director of the Jewish Board of Guardians, holding the position from 1943 to 1965. As the organization’s leader, Alt modernized child guidance practices and incorporated psychiatric approaches into residential programs. He was particularly interested in psychoanalysis, which was gaining prominence in the mid-20th century, and sought to apply these theories to treat troubled youth more effectively. Alt was a systems thinker who had a keen eye for how best to develop, integrate, and support programs within and across institutions, communities, and governmental agencies. Under his leadership the Jewish Board of Guardians introduced some of its most important programs and services. A summary of Alt’s contributions and unique place in Jewish Board of Guardians history was stated eloquently by former Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services Executive Director Jerome Goldsmith, who eulogized Alt after his death in 1981:

Herschel Alt was part of a handful of pioneers in the human services who made a special imprint upon their respective fields. He came to the Jewish Board of Guardians and he had a dream about how children could be helped… He was always an innovator, who talked about the “limits of treatability.” He meant, of course, pushing the limits of treatability as far as possible, beyond the expectations of the professional experts, beyond the fiscal resources of the budget minded. He projected a deep professional investment in programs for the most severely disturbed children and adolescents, who moved like strangers among their age peers, children who could not make contact with the rest of the world… to provide an environment that will help these children build bridges to reality so they are no longer strangers among us.

Early Life and Career

Herschel Alt was born in Russia in 1897 and emigrated to Ontario, Canada with his mother and siblings at the age of seven. There, he reunited with his father, who had left Russia when Alt was an infant. Hardship shaped his early years, particularly the family’s struggles with tuberculosis. Over the course of just a few years, the highly infectious disease killed 3 out of 4 of his siblings and his father, and nearly killed him. This experience would later drive his interest in social welfare.

Alt was a curious and gifted student who took an active role from a young age in Jewish social causes. His career began in Toronto, where he worked for the local branch of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies before resigning in protest of their policy excluding women from decision-making roles. After graduating from the University of Toronto’s Law School in 1919, a recurrence of TB sent him to Tucson, Arizona, where the dry climate aided his recovery, and his career in social welfare and child guidance began in earnest – influenced by prominent figures in the field such as CC Carstens and Lawson Lowrey.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Alt held supervisory roles at various social service organizations across the United States, from the Juvenile Protective Association in Los Angeles, a role he accepted at the advising of Dr. Carstens, to the Louisville and Jefferson County Children’s Home in Kentucky. He also served as head of the St. Louis Children’s Aid Society, a challenging role he held during the Great Depression years.

Hawthorne Cedar Knolls and Transforming Treatment

Alt’s tenure at the Jewish Board of Guardians began with his appointment by John Slawson to lead the Hawthorne Cedar Knolls residential treatment program in 1941. The institution had a reputation for strict discipline and custodial care, relying on punitive methods that Alt found outdated. He believed a psychodynamically-informed trusting relationship with the program’s children would yield much better results, including the development of a nurturing therapeutic environment where their emotional and psychological needs could be more effectively contained and addressed. He immediately began transforming Hawthorne Cedar Knolls by replacing harsh discipline with treatment based on such principles, to good effect.

One of Alt’s key innovations was to more fully integrate the staff’s efforts and responsibilities. He recognized that the residential staff who worked most closely with the children (known as “cottage parents”) often felt marginalized compared to the social workers and clinicians. Alt took the time to understand the frustrations of these staff members and invite their voices into a more unified treatment approach, ensuring that the therapeutic and disciplinary elements of care were aligned across disciplines. This systems-based thinking allowed the institution to shift from a punitive environment to one that emphasized open communication, emotional healing, and psychological growth.

Leadership as Executive Director: A Focus on Post-War Adaptations

Alt assumed the role of Executive Director in 1943 against the backdrop of World War II, after Dr. Slawson left to take a new position as executive director of the American Jewish Committee. The number of delinquent youths requiring institutional care declined noticeably during this time, largely due to the creation of community outreach programs, including collaborations with police and the courts. Instead, the agency saw an increase in younger, more severely disturbed children who required different treatment approaches. In the years after the war, Alt responded by focusing the agency’s mission on further refining diagnostic tools and treatment methods, ensuring that it could meet the evolving needs of its clients.

A central part of Alt’s philosophy was the idea of creating a “conditioned milieu” for children in their care. This concept went beyond the “conditioned environment” model that Slawson and other predecessors had emphasized. Whereas that model focused on helping children adapt to the existing environment, Alt’s approach emphasized the importance of shaping the environment to promote healthy psychological development and create space for clients and staff alike to explore intergroup dynamics as part of a community. Alt also advocated for the development of evidence-based practice and invested in developing tools to measure treatment outcomes, recognizing that the lack of such tools within the field of psychiatry was a huge obstacle to understanding the efficacy of treatment approaches.

Alt encouraged his staff to make use of research opportunities endowed by the nascent National Mental Health Institutes, which was created in 1949, and particularly encouraged research that could help refine existing programs toward the development of a more individualized “continuum of care.” With the need for tailored treatment in mind, Alt successfully pushed for the creation of new programs that bridged research and clinical care for the youngest of children all the way to emerging adults. These included the renowned Child Development Center, Henry Ittleson Center for Child Research, and the Linden Hill School.

Challenges and Innovations in the 1950s and 1960s

In the post-war period, Alt’s leadership focused on expanding and refining the Jewish Board of Guardians’ programs to better serve children with complex emotional needs. One of his key contributions was the Unit Plan of staff organization, which recognized the psychiatrist as chief clinician but positioned it in a more collaborative, rather than authoritative, role in relation to other staff. This multidisciplinary approach helped integrate psychiatric, psychological, and social work disciplines into a cohesive treatment plan for each child.

Despite these advancements, Alt was keenly aware of the challenges in measuring the effectiveness of treatment programs. He often expressed concerns about the lack of reliable tools to gauge long-term outcomes and pushed for more rigorous evaluation methods.

After World War II, his insights into child welfare had begun to gain international attention. He served as a consultant to the Israeli government, helping shape their child welfare services, and worked with the U.S. Army during the occupation of Germany to advise on child welfare and psychological care for displaced persons. He was also involved with the World Health Organization, contributing to international discussions on child psychology and rehabilitation.

Alt’s interest in cross-cultural developmental differences was reflected in his later work, particularly with his wife, Edith. Together, they wrote The New Soviet Man: His Character and Upbringing and Russia’s Children, which explored child-rearing practices in the Soviet Union and their impact on psychological development. Alt was also involved in projects examining child development in Israeli kibbutzim, where the communal child-rearing model offered a unique perspective on collective versus individual approaches to psychological growth.

Legacy

Herschel Alt’s priority as leader of the Jewish Board of Guardians was to ensure the provision of high-quality psychotherapeutic treatment for children with a range of mental health struggles, and he was largely successful in carrying out this lofty vision. But by the time of his retirement, this aim was becoming increasingly incompatible with funding models and priorities that had begun to take root, and he would reflect in later years that perhaps the ambitiousness of the Jewish Board of Guardians to help as many children as possible had set the organization up for a particular set of challenges and difficult decisions in the years that followed his tenure.

Alt left the agency in 1965, at a time of great change and transformation. Funding models were rapidly shifting and the provision of high-quality services across programs was becoming more of a challenge. Changes would have to be made under subsequent leadership.

The internal records of the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services contain over five hundred pages of draft material Alt had prepared for an intended memoir/autobiography. He was in talks with an editor at the time he passed away in 1981, and it remains unpublished. Correspondence between JBFCS Executive Director Jerome Goldsmith and Alt’s family members also reveal that at one time, there were plans being put in place for the establishment of a Herschel Alt Research Institute. Perhaps more than any of the other architects of care featured in this project, Alt drew very clear and specific conclusions about how his early life experiences informed his decision to work in child guidance. Chief among these include the moral and ethical teachings of Judaism, his experience in Russia during the turn of the century, and his observation of how environmental and societal circumstances have the potential to cause either psychological harm or healing. Excerpts from his draft memoir and his oral history help tell this story.