At the beginning of the 20th century in the United States, social work emerged as a formal profession with roots in the settlement house movement and charitable organizations. Early social workers primarily focused on addressing the needs of individuals and families in rapidly industrializing and urbanizing environments. Their roles included providing direct practical support such as food, clothing, and housing to those in need, and advocating for reforms that would bring about better social conditions. Eventually, they would help to establish child guidance clinics like the one the Jewish Board of Guardians founded in 1926.

Following World War I, psychiatric casework became an essential component of mental health care, including at dedicated child guidance clinics, driven by increased awareness of mental health issues and the need for specialized intervention. This period marked a significant shift in social work towards professionalization. Key developments included the creation of formal education and training programs, the establishment of practice standards, and the formation of professional organizations. A major milestone in this evolution was the founding of the American Association of Social Workers (AASW) in 1921, which merged with several sister organizations to become the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) in 1955. Casework was one key component of professional social work that was developed during this period, and is defined by the NASW as a “method of providing services whereby a professional social worker assesses the needs of the client and the client’s family, when appropriate, and arranges, coordinates, monitors., evaluates, and advocates for a package of multiple services to meet the specific client’s complex needs.”

Additional advances to casework techniques were made in the 1920s and 1930s, including structured methods for assessing and addressing psychological and social needs. These techniques involved improved interviewing, case recording, and therapeutic interventions. Several higher education institutions had by this point incorporated formal social work programs into their offerings. By the 1930s, Smith College, New York University, Columbia University (New York School of Social Work), and Howard University had all developed working relationships and/or affiliations with the Jewish Board of Guardians. Both JBG and The Jewish Social Service Association, the two JBFCS predecessor organizations of the time, were recognized for their progressive approach, granting highly trained social workers—who were predominantly women at the time—the autonomy to lead groups, serve as clinical case workers, and assume roles in leadership, research, and training of other social workers.

American social workers also embraced psychoanalytic theory. The analytic émigré community discovered a generally supportive, likeminded, and welcoming environment within social service agencies and child guidance settings. This contrasted with adult mental health treatment, where the field was dominated by American, medically trained male psychiatrists and lay analysts, and where training requirements were more restrictive. This period saw the integration of psychoanalytic ideas into social work practice, significantly shaping therapeutic approaches. The Jewish Board of Guardians was one of the first agencies to intermarry these two groups directly by bringing social workers and psychiatrists as equals together into the treatment of children, fostering an environment where they could learn from one another. This approach seemed to offer a model for treatment that was very successful in what it could offer to the population of mostly Jewish children and parents struggling with complex mental health problems.

The Jewish Board of Guardians and Jewish Social Service Association were more progressive than many other agencies providing mental health services in the mid-century, in that from the outset they granted social workers and lay child welfare workers—who were predominantly women—the authority to conduct individual psychotherapy and to lead groups, and to go on themselves to assume roles in leadership, research, and training. JB also conducted research into the effectiveness of various clinically trained professionals, advocating for the empowerment of social workers in leadership roles. This research underscored the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and the advancement of social workers as case managers.

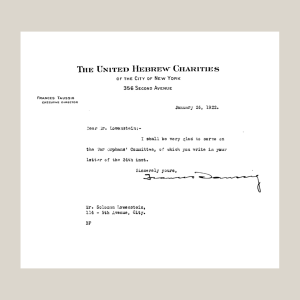

Under the leadership of social worker Frances Taussig, during the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Jewish Social Service Association and its team of mostly women social work leaders played a crucial role in the resettlement and integration of recent immigrants. In collaboration with the National Refugee Service (later the National Coordinating Committee) and other Jewish aid organizations, JSSA expanded its services to meet the needs of refugees and other displaced persons, including through its Committee on Mentally Sick refugees. Notably, archival documents in the YIVO Institute’s collection indicate that JSSA had an arrangement with the NRS until at least 1939 in which the JSSA’s social workers would treat undocumented Jewish immigrants, because their files would be less likely to get noticed by government officials. JSSA also created training and internship opportunities for refugee social workers and psychoanalysts, and Taussig chaired its Committee on Displaced Foreign Social Workers, which sought to facilitate the emigration, hiring, and assimilation of Jewish social workers coming to the US from Nazi-occupied Europe.

Despite progressive advancements in organizational structure, psychoanalytic thinking and child mental health practices of the time often reinforced rigid gender roles and societal expectations in the post-war years. The focus on consumer capitalism and “momism,” a term coined in 1942 by writer Philip Wylie to describe society’s excessive and sentimentalized devotion to mothers or motherhood, led many to blame the stereotypical smothering and overprotective maternal figure for child mental illness; these trends reflected broader societal beliefs about family structure and gender roles. And allthough women were allowed to lead groups and conduct therapy, it took decades for feminist critiques of psychoanalysis to be integrated into mainstream narratives.

By the early 1960s, as civil rights movements gained momentum and the mental health system faced increasing strain, labor issues began to surface. “On February 16, 1962, workers at Hawthorne Cedar Knolls, including social workers, nurses, maintenance staff, and a psychologist, went on strike due to overwork, inadequate pay, and dangerous conditions. The strike lasted ten days, after which the administration considered closing the center and relocated twelve children to another residential treatment center. A similar strike occurred in March 1964, during which administrators reportedly used medication to calm children who felt abandoned by their cottage parents.”