Drawing on his legal expertise and understanding of the New York court system, George Zerdin Medalie championed a shift towards preventative social work, emphasizing early intervention and individualized treatment to address the root causes of behavioral issues in children.

President, Jewish Board of Guardians, 1931-1939

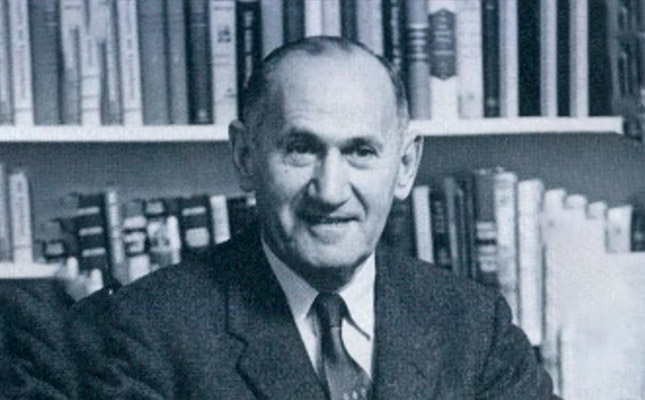

George Zerdin Medalie (1883-1946) was a prominent attorney, judge, civic leader, and president of the Jewish Board of Guardians. By the time he was appointed to lead the agency in 1931, he had just been promoted to US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and had already earned a reputation as an anti-racketeering prosecutor and investigator of election fraud – and as a talented trial lawyer who had taken on the corruption in Tammany Hall and mentored future New York governor Thomas Dewey.

Like many other presidents of social welfare agencies, his effectiveness did not stem from clinical training or expertise. Instead, having established himself as a prominent defender of Jewish social causes and legal expert with robust knowledge of the New York court system and its inner workings, he was able to use his voice to advocate for the visions of his clinical contemporaries, particularly Jewish Board of Guardians Executive Director Dr. John Slawson. The decade of his leadership at the JBG was dominated by the embrace of the child guidance movement, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis. Medalie, in his role working with Jewish charitable causes, was also attuned to growing anxieties about the security of Jews in Europe and at home in the wake of the passage of highly restrictive immigration policies and the rise of Nazism in the 1930s.

Early life and Career

George Zerdin Medalie was born on Henry Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1883. The son of Russian immigrants, Rabbi Aaron Medalie and Rachel Zerdin, Medalie spent much of his time as a child at the Educational Alliance, a historic community institution that was founded in 1889 as a settlement house for East European Jews immigrating to lower Manhattan. He excelled in grade school and won the Pulitzer Scholarship, which secured his admission to Columbia University. Upon graduating Phi Beta Kappa, he went on to Columbia Law School. After earning his law degree, Medalie started a private practice and quickly advanced in the field of commercial law, attracting the attention of prominent jurists, public officials, and Tammany Hall. From 1926-1928, he served without compensation as a Special Assistant Attorney General, investigating and prosecuting fraudulent election activities in Manhattan and the Bronx.

In 1931, President Herbert Hoover appointed George Medalie as the United States Attorney for the Southern District. That same year, following the death of his predecessor Mortimer Schiff, Medalie became the acting head of the Jewish Board of Guardians. By October 1931, he was elected President of the board and held the position until 1939.

Influence on Clinical Care

With a distinguished background in the courts and trial law, George Medalie ardently supported the preventative approach to child guidance. Speaking in March 1937 before a group of 1000 youth at the Brooklyn Jewish Center on Eastern Parkway, Medalie declared that “modern social work, like modern medicine, has discovered from experience that preventive work is the greatest contribution we can make to society.” A precursor to early intervention, prevention helped keep children out of the juvenile justice and mental health system in the first place.

In this push to divert children from the criminal justice system, Medalie also advocated for individualized treatment of behavioral problems, and he drew an explicit link between the agency’s approach over the past twenty-five years and the decrease in juvenile delinquency and crime rates among Jewish children and adults. He also promoted collaboration and knowledge sharing across institutions in the criminal justice system, and helped to formalize the clinical objectives of executive director John Slawson. These included the formal integration of psychoanalytic principles into treatment, and greater collaboration across disciplines.

Under Medalie’s leadership, the Jewish Big Brothers1 also expanded to Brooklyn. One of the first mentoring organizations in the United States, the New York City chapter of the Jewish Big Brothers was a predecessor organization to the Jewish Board of Guardians. Since its founding in 1907, its mission has been to provide preventative mentorship to young boys in need, fostering positive relationships that help them lead meaningful and healthy lives, and support for at-risk youth as an alternative to the juvenile justice system. Medalie viewed this expansion of the Jewish Big Brothers as an important “step toward more flexible and individualized handling of young offenders…” and an important opportunity for adult members of the community to contribute: “Big Brothers who will establish this intimate confidential relationship with their ‘little brothers’ come from every walk of life—merchants, bankers, physicians, lawyers, teachers, students—all willing to undergo special training to enable them to cope with the problems of the maladjusted boy,” he said in an interview about the program. Medalie recognized that the opportunity to participate as a Big Brother had mental health benefits to the Big Brothers as well as the Little Brothers – providing a sense of purpose, aid, and interpersonal connection through the work.

Medalie’s Legacy

In 1941, Medalie was elected the 11th president of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, serving until 1945. He also held many other important posts in the Jewish communal world, including as member of the Mayor’s Committee on Unity and the American Jewish Committee.

Medalie’s professional identity was multifaceted; one important aspect of his work as president of Jewish Board of Guardians as well as the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies was in raising funds for Jewish charitable causes—as well as raising awareness about the conditions Jews faced in eastern Europe and reminding people of what he saw as the moral responsibility to care for those in need at home. In a powerful keynote speech at the Hotel Statler on November 10, 1935, kicking off the 1936 campaign of the Jewish Federation for Social Service to Help Fight Human Misery with 700 people in attendance, Medalie declared that

Charity is erroneously named. It should be called justice. It doesn’t mean a patronizing; it means equalization; a tendency towards a leavening process… In proportion to what we have, we have obligations… The obligation is to the place in which we live, to the people with whom we live and to the things needed to bring them to the level of human dignity.

At the time of his sudden death from a heart attack in 1946, George Medalie had just finished his fourth term as President of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies and had five months earlier been appointed to the New York State Court of Appeals—the highest judicial position in the state. He left his wife and two daughters, one of whom would go on to fight for gender equity in tennis and left a mark on the Jewish Board of Guardians for his unique ability to bring attention to the agency’s work, advance new aspects of its clinical interventions, and demonstrate a morally driven commitment to improving the lives of children the agency served.

- The Jewish Big Brothers was founded in Cincinnati in 1903 by Irvin F. Westheimer, a young Jewish man who was inspired to help a young boy he saw scavenging for food. Westheimer and a group of friends began informally mentoring young boys in need, and the Jewish Big Brothers quickly became a nationally chartered group and beginning in 1910 was an important social service in New York City. ↩︎

Reference List, Bibliography and Research Resources

- American Jewish Yearbook Volume 48, 1946. Prepared by the staff of the American Jewish Committee under the direction of Harry Schneiderman and Julius R. Maller, Editors, Philadelphia, The Jewish Publication Society of America. https://archive.org/details/americanjewishye0000unse_p7l1/page/98/mode/2up

- Bienstock, Victor. “An Outline of Post War Plans,” The Jewish Press, Omaha, Nebraska, February 27, 1942

- Cohen, Simon. “Jewish Pioneers in the Big Brothers Movement.” American Jewish Historical Quarterly 61, no. 3 (1972): 223–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23877811.

- George Zerdin Medalie, Historical Society of the New York Courts, https://history.nycourts.gov/biography/george-zerdin-medalie/ Accessed August 15, 2024.

- “Jail Chaplains Exchange ideas at conference,” The Brooklyn Citizen, Brookly, NY, March 3, 1937

- “Jewish Charity Leaders Open 1936 campaign,” Buffalo Courier Express, Buffalo, New York, November 11, 1935

- “Jewish Welfare Service Extended,” Times Union, Brooklyn NY, Monday, September 2, 1935

- Judge George Z. Medalie, Outstanding Jewish Leader, Dies; Was Active in Civic Affairs, JTA https://www.jta.org/archive/judge-george-z-medalie-outstanding-jewish-leader-dies-was-active-in-civic-affairs

- “Social worker talks to 1000 Jewish youth,” The Brooklyn Citizen, Brooklyn, New York, Tuesday, March 30, 193

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry. New York: Basic Books, 1982.

- “US At War: Men Around Dewey.” Time Magazine., May 29, 1944 https://time.com/archive/6788442/u-s-at-war-men-around-dewey/ Accessed September 1, 2024.