The Jewish Board of Guardians’ Child Guidance Clinic, established in 1926, was one of the earliest of its kind in the United States. It was part of a broader movement in child welfare that was aligned with Progressive Era principles and influenced by psychoanalysis, a therapeutic approach (first developed in Vienna at the turn of the 19th century by Sigmund Freud) that explores unconscious thoughts and feelings to understand and resolve psychological conflicts and symptoms.

Child guidance workers built on progress from the settlement house movement, the professionalization of social work, and evolving ideas about how children should be treated. The federal government was also extremely involved in this movement, founding the United States Children’s Bureau in 1912. Advocates for this emerging interdisciplinary field—comprising professionals in social work, psychiatry, psychology, the juvenile court system, and schools—rejected earlier punitive approaches to child welfare. Instead, they collaborated to create and operate specialized child guidance clinics that provided therapeutic interventions for children with behavioral and emotional issues.

At the same time, the child guidance era was built in part on the foundations of the “psychiatric-carceral state” which had emerged at the turn of the 19th century. This term is used by historians today to describe the collusion of psychiatry, social work, and the criminal legal system to reform and rehabilitate girls who were perceived as wayward, difficult, or socially deviant, in response to anxieties about “juvenile delinquency.” And fundamentally, the child guidance approach accepted as objective truth the idea that many of the behaviors of young girls at this time were troubling and even criminal, rather than questioning, critiquing, or seeking to abolish structures that in the first place deemed such natural and developmentally appropriate behaviors as deviant. It also reinforced traditional stereotypes and ideals about gender and the white, Christian, American family.

During this period, Jewish Board of Guardians clinicians contributed directly to the development of several key aspects of the evolving child guidance movement. Its program was like other child guidance clinics across the country which, in an effort to provide meaningful care, emphasized qualities like a more evidence-based and scientific approach, adherence to high standards of professional training (the American Association of Social Workers was founded in 1921); education and advocacy; and interdisciplinary collaboration among psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, pediatricians, sociologists, nurses, and educators.

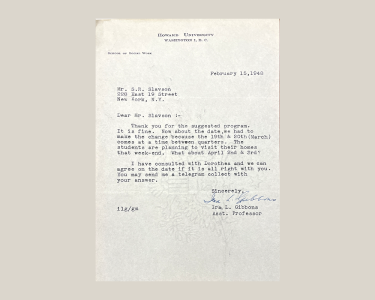

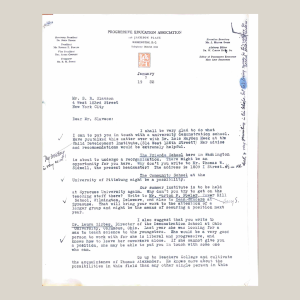

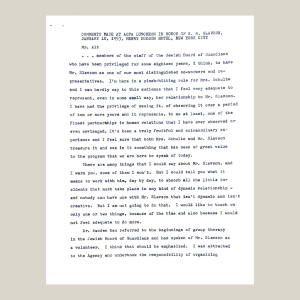

In this respect, the Jewish Board of Guardians may have differed from many of its counterparts across the country. The approach different child guidance clinics took also reflected the needs and contexts of the communities in which they were developed and the populations they were seeking to help. With its roots as an organization led by Jewish immigrants working to address “juvenile delinquency” rates specifically within the local Jewish immigrant population, the Jewish Board of Guardians attracted a group of likeminded child guidance clinicians who had comparatively progressive and communal values, and a shared vision for a somewhat different way of working with children. This group included Herschel Alt, SR Slavson, known as “the grandfather of child group therapy,” his brother and JBG Executive Director John Slawson, and social workers like Betty Gabriel and Madeleine Borg.

The development of child group therapy in the 1930s was one of the movement’s major contributions and reflected the agency’s relatively progressive and empathy-driven ethos. Director of Group Therapy, SR Slavson described the model in the following way:

Children whose difficulties arise from conflict with the family group can be helped in many instances by making it possible for them to live with an intimate group where they are able to re-establish group attitudes and learn group behavior. This can be done only in an atmosphere of freedom and full acceptance. Thus, in Group Therapy, as we employ it in our agency, the client receives from the adult what we call “unconditional love,” (which is manifested by the fact that no matter what the child does in the early stages of his membership in the group, he is not reprimanded, disapproved or punished.)

We say that children are neither bad nor good’ they simply are what they are and to help them we must accept and love them as they are. We have found that this attitude of tolerance and whole-hearted acceptance gradually permeates the relations of the boys or girls with one another.

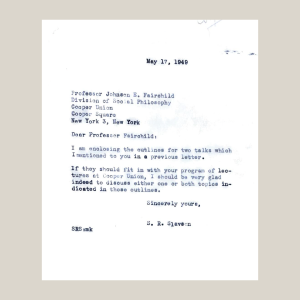

Slavson would eventually found the American Group Therapy Association, and colleagues at the JBG adapted the model for use with adults and specialized treatment groups, including for those with personality disorders, substance use problems, and histories of trauma. Other institutions developing similar group therapy programs for adults, including WIlfred Bion and the Tavistock Clinic, would eventually share notes. But SR Slavson is credited with this original model of activity group therapy, which became a cornerstone of JBG’s treatment.

Slavson and other midcentury Jewish Board of Guardians child guidance clinicians were informed by progressive educators such as Maria Montessori, John Dewey, the Walden School which reframed the hierarchies of authority structures; of child welfare leaders C.C. Carstens and William Healy of the Child Welfare League of America; and of psychoanalysts, especially August Aichhorn, who in Vienna worked at the intersection of psychology and progressive education and opposed the “juvenile delinquent” lens that prevailed during the early 20th century. He was known for encouraging creativity, for improvising and following his intuition, rather than adhering to dogmatic approaches, in clinical work with antisocial boys.

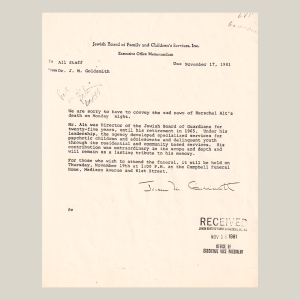

Despite all of these advances, the movement faced challenges, and the implementation of this framework shift from punitive to rehabilitation did not happen overnight. For instance, the Hawthorne Cedar Knolls residential programs struggled to transition from a disciplinary to a more supportive approach. At Hawthorne Cedar Knolls, corporal punishment was once common, and there was even a small jail on the grounds, a small, free-standing cell that had been used to temporarily (“for a matter of hours”) hold violent and uncooperative residents, as noted by Dr. Herschel Alt, who worked at Hawthorne from 1941 to 1943 before becoming the Jewish Board of Guardians’ Executive Director in 1943. (By the time he arrived at Hawthorne, it was being used to hold agricultural equipment and was no longer active.)