On March 2, 1914, Lena Adler, age 29, walked into the offices of the National Desertion Bureau in downtown New York.

Lena sat down at the desk of a Desertion Bureau investigator. She told the investigator that her husband Morris had disappeared a month prior. She had not heard from him since.

Morris had run away for a few weeks at a time, in 1912 and later in 1913. Lena had already opened a case with the Desertion Bureau, but Morris returned. Now, she did not know if he would come back.

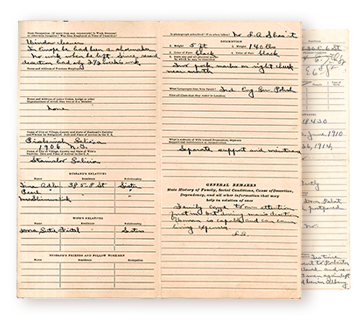

In her interview with the investigator, Lena described her husband as follows: Five foot seven inches in height, 140 pounds, black hair, black eyes, and two pock marks on his right cheek.

Morris had immigrated to New York City from Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1906. He joined a wave of Jewish and other European migrants that began in the nineteenth century and continued until the First World War.

Lena, also an immigrant from Galicia, met Morris in New York and married him in 1910.1 Two children soon followed: Jake, in 1911, and Isidore, in 1913.

Morris washed windows for a living but had no work when he deserted. Lena found herself alone, with two small children to care for, and no source of income. Destitute, she turned to the United Hebrew Charities for help.

The organization began to give Lena a monthly allowance, and referred her to its sister agency, the National Desertion Bureau, to track down her husband and force him to pay child support.

- Jewish reformers worried that desertion would be perceived as a characteristically “Jewish” issue. They argued that desertion was instead a temporary aberration, the result of immigrant husbands arriving in America many years before their wives. In reality, the majority of the National Desertion Bureau’s caseload was made up of couples who had met and married in America, like Morris and Lena Adler. ↩︎

The United Hebrew Charities had been dealing with the issue of men deserting their families since its founding in the 1870s. By the early 20th century, its leaders had come to see desertion as a full-blown societal crisis.

When a man abandoned his wife, he left the entire family destitute––or at least that’s what Jewish leaders believed.1 These impoverished women began knocking on the doors of the United Hebrew Charities and other organizations. If husbands could be forced to support their families, the thinking went, then the Charities would not have to spend as much money supporting them.

In 1911, these leaders created the National Desertion Bureau. The organization would track down Jewish men who had abandoned their wives, and force them to pay child support. It immediately became popular, with more than two thousand women opening cases with the Bureau in its first five years.2

The staff members of the Bureau had their work cut out for them. Men deserted their families for all kinds of reasons––another woman, economic difficulties, gambling, drinking, “interference of relatives,” and even “wanderlust.” In an age before mass telecommunication, and before Social Security and the bureaucratic tracking of individuals it entailed, leaving one’s family, perhaps changing one’s name, and moving to a different city or state (or even down the road) was surprisingly easy.

- In reality, many deserted women supported themselves effectively despite the difficulties they faced in finding employment, and only sought help from the Desertion Bureau as a last resort. ↩︎

- Based on an analysis of cases from the National Desertion Bureau’s card catalog. Most women were referred to the NDB by a partner agency like United Hebrew Charities. ↩︎

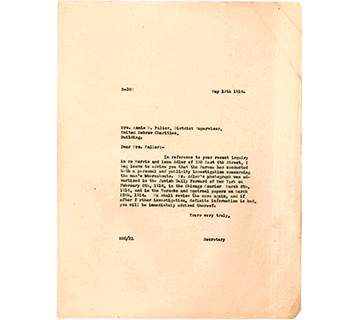

The Bureau’s investigators moved quickly to help Lena Adler. They advertised the case in Jewish newspapers in New York City, Chicago, Toronto and Montreal.

Morris Adler had already made his debut in the Jewish Daily Forward’s infamous “Gallery of Missing Husbands.” The Gallery, established in 1908, helped readers find deserters and report them to the authorities. The Forward hoped that publishing the names and mugshots of the deserters would shame these men into supporting their families.1 Of course, the stories in the Gallery also served as entertainment for the newspaper’s audience of more than a million readers.

On February 18, 1914, Morris’ mugshot appeared in the Gallery alongside five other deserters. The description of his case read:

Morris Adler, 30 years old, disappeared, abandoning his wife Lena and their two small children in October 1913. His family has been supported by United Hebrew Charities the whole time. Adler was born in Galicia and is a window cleaner by trade.2

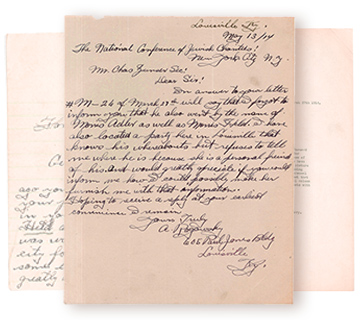

A few weeks later, A. Rogowsky, a Metropolitan life insurance agent from Louisville, Kentucky, wrote into the Forward.

Rogowsky’s letter told the story of a man named “Morris Held,” who had arrived in Louisville, married his sister, and disappeared without a trace shortly thereafter.

After the disappearance, a friend had seen Morris’ picture in the Gallery of Missing Husbands. The family was shocked to discover that Morris already had a wife and children in New York. Mr. Rogowsky appealed for help to locate this man and have him arrested for bigamy.

The Forward referred the case to the Desertion Bureau, which did not immediately connect the dots. But Mr. Rogowsky wrote back to confirm: Morris Held and Morris Adler were one and the same.

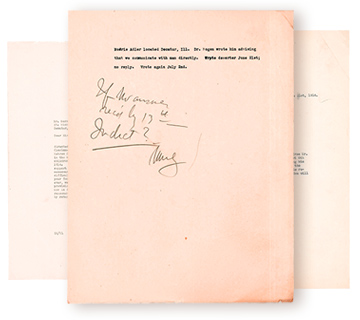

The Desertion Bureau activated its network of local affiliates to track Morris down. In May 1914, investigators located him in Cincinnati, Ohio, and then in Decatur, Illinois.

Knowing he had been found, Morris wrote in and identified himself. The Desertion Bureau replied, giving him one last chance to “make provision for the support of your wife and children, who are now in destitute circumstances.”

Morris had other plans.

The investigation triggered a series of dramatic escapes, taking Morris on a journey across the United States. Using their vast network,1 the Bureau’s investigators tracked him to each of these locations. In every instance, he gave them the slip right before he was caught.

In October, Morris returned to Louisville to pursue his second wife, but she refused him. The authorities found out, but Morris left before he could be arrested.

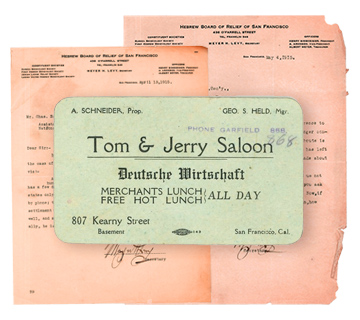

In December, Lena Adler reported that her husband had returned to New York and could be found at a saloon at 332 Bowery, Manhattan. A detective staked out the location, but Morris did not appear. In April 1915, the Bureau received word that Morris had relocated to San Francisco. Following the path of many others headed west, Morris attempted to reinvent himself. Living under the alias “George S. Held,” he was now the co-proprietor of the “Tom and Jerry Saloon.”2 His business partner had few complaints, although he did note that Morris “has too many women ringing him up by phone.”

Just as the police were about to arrest him, Morris disappeared again.

- The Bureau’s remarkable ability to track down deserters was arguably the most successful aspect of its work. To track the missing men, the Bureau worked with investigative staff at hundreds of organizations and agencies nationally and internationally, and made use of information provided by many different types of individuals. Annette Igra’s study of the Bureau showed that it succeeded in tracking down deserters in more than three quarters of its cases. ↩︎

- Morris’ saloon predated the famous cat and mouse cartoon by 25 years. Like the name of the cartoon, the name of the saloon was probably inspired by characters from the popular illustrated book Life in London by Pierce Egan, first published in 1821. “Going Tom and Jerry” came to mean going wild, living the high life. ↩︎

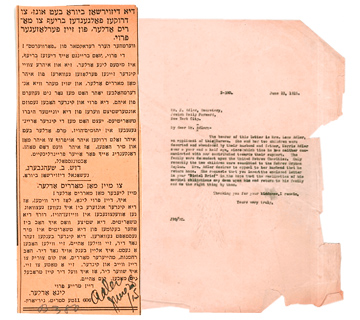

In June 1915, the Desertion Bureau asked the Forward to publish a personal letter written by Lena Adler to her husband.

The letter read:

My dear husband Morris Adler:

I, your wife Lena, want to let you know that our children have been forced into an orphanage by the charities. The support I have received from the Charities has been stopped. The children miss you very much, they want to come home, they want to have a nest. I also miss you very much. Have mercy, dear Morris, and come back to your wife and children. Be a father to them. I swear to you, I will not cause you any trouble. Come home.

Your faithful wife,

Lena Adler.

How much truth this letter contained, how many of the words were Lena’s own, is unclear. Most likely, the Forward’s editors had heavily doctored it to tug at Morris’ heartstrings—and at the heartstrings of the newspaper’s readers.

The letter did not work. But the publicity helped the Bureau track Morris down again. In August, a Mr. Etvinkrantz of Chicago wrote in to report that Morris now lived in the city. Morris had told Etvinkrantz that he had not been in touch with his family because he was in “bad circumstances.”

“A very convenient course,” the Bureau’s investigator commented.

The Bureau tracked Morris to Elgin, Illinois, where the law finally caught up with him.

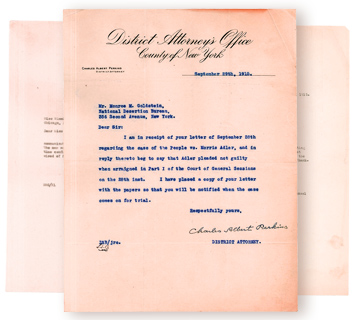

In September 1915, the police extradited1 Morris to New York City and imprisoned him in the Manhattan House of Detention–– the “Tombs”––where he awaited trial.

- The extradition of Morris Adler was atypical. In 1903, United Hebrew Charities’ lobbying helped make child abandonment a felony, allowing legal authorities to extradite deserters over state lines. But the resultant 1905 Child Abandonment Act never really worked in practice. Prosecuting authorities mostly saw desertion as a private family matter that did not warrant serious punishment. Less than one fourth of deserters found out of state were extradited. ↩︎

The trial of Morris Adler on the charge of “willfully abandoning his infant children in destitute circumstances” began on October 6, 1915. Charles Zunser, director of the National Desertion Bureau, served as a witness.

By this point, Morris had been away from his family for nearly two years. Unable to support her children, Lena had placed them temporarily in an orphanage.

On the 7th of October, the court called Lena to the stand. She told the judge that she had changed her mind. Lena had visited Morris in the Tombs, where he had promised to reconcile with her if he was released.

Perhaps out of financial desperation, or perhaps out of genuine affection, Lena asked the court not to prosecute.

“In view of the wife’s present attitude, it will be most difficult to obtain a conviction,” the Bureau’s investigator wrote disapprovingly in his notes.

Nevertheless, on October 20th, 1915, the judge convicted Morris Adler and sent him to the penitentiary for four months.

With Morris in prison, the destitution of the family had become “extreme.”1 United Hebrew Charities provided Lena with a $6 check to help with the rent, but she refused to accept it.

Lena, it seems, believed that her problems would be solved if only she could have Morris home. She visited the Bureau multiple times to request help in securing his release.

On February 15, 1916, Morris walked out of the Penitentiary. On the 29th, the Bureau’s investigator found him at home with his wife and children.

Things were “alright,” Morris reported. But the final case note from that year included an ominous line: “blamed wife for trouble – woman knew.”

What did Lena know? The note doesn’t say. But one thing is clear: after everything that had happened, an easy, happy ending to this story would be unlikely.

- The Desertion Bureau case file records Morris’ profession, but at no point does it tell us about the work Lena did outside of the home to support her family. This omission reflects the gender bias of the Bureau – it placed the breadwinning role firmly in the hands of husbands, not wives. ↩︎

After 1916, the Adler’s case file goes quiet for 12 years.

On December 25th, 1928, Lena returned to the offices of the Desertion Bureau, this time with Morris. The couple had separated, and Morris had gone to live with his sister.

The Bureau’s investigator had few kind words to say about Morris. But he also thought Lena was “narrow-minded.” She had become ambivalent about reconciling with Morris, even though the investigator felt that “under the circumstances” reconciliation “appears to be the most logical thing to do.”

These words summed up the Bureau’s attitude to desertion since its founding. Repairing a couple’s romantic bonds had never been its priority. It viewed stable marriages as the solution to poverty. The feelings of the parties to a marriage were secondary.

Lena Adler had a different set of priorities. With the weight of her many years of bitter experience, reconciliation with Morris did not seem as attractive as it once had.

Four years later, Lena submitted a petition of naturalization to the US District Court in New York. The petition included the following note: “I left my husband in 1929 and have not seen him or lived with him since. No divorce and none pending.”

In spite of her difficult life circumstances, in spite of pressure from the National Desertion Bureau, in spite of the fact that obtaining divorce from Morris would be nigh impossible,1 and in the face of society’s expectations, Lena had taken control of her own life.

- Desertion became known as the “poor man’s divorce,” because of the prohibitive cost of legal divorce at the time. There was also the obstacle of obtaining a “get,” a Jewish religious divorce, which was and remains to this day the man’s prerogative. ↩︎

In many ways, Lena Adler got exactly what she wanted from the United Hebrew Charities and the National Desertion Bureau. Through its skillful detective work, the Bureau tracked down Morris and brought him to justice.1 The Charities supported Lena and her children in the meantime.

But neither organization could make Morris Adler the kind of husband and father that Lena needed him to be. The Adlers’ case places the central limitation of the early 20th century desertion system in stark relief. This system attempted to make the wellbeing of women and children a private matter, dependent on the actions of a husband, rather than the responsibility of society at large.

Eventually, tracking down fathers and forcing them to pay child support became the purview of the state. But our society continues to promote and rely on hetrosexual marriage as the way to fix poverty. The story of the Adlers can help us to raise an important question: what if the wellbeing of struggling women, children and families was all of our responsibility?2

- Because the NDB’s administrative records are missing, our understanding of how the organization worked on a day-to-day basis is limited. However, we are able to piece together some of these details from the casefiles themselves. ↩︎

- To learn more about the history of the National Desertion Bureau and its broader historical context, read Wives without Husbands: Marriage, Desertion, and Welfare in New York, 1900-1935, by Annette Igra. ↩︎

How do we know about Lena and Morris Adler?

The Adlers’ file is one of more than 19,000 National Desertion Bureau case files held by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City. As you have seen, these files contain rich details about the lives of ordinary people in New York City and beyond, details not available anywhere else.

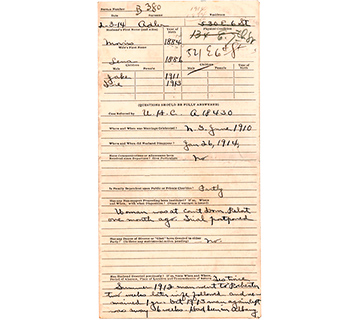

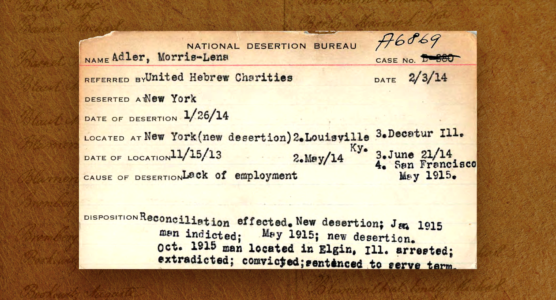

The Desertion Bureau also created a card catalog to help manage its caseload. Here is the card for the Adlers, from 1914.

We have created a database of this card catalog. Take some time to search the database. Perhaps your own family is part of the remarkable story of the National Desertion Bureau.

- 1. Desertion and Despair

- 2. A Family’s Struggle

- 3. The National Desertion Bureau

- 4. The Gallery of Missing Husbands

- 5. Bigamy in Louisville

- 6. One Last Chance

- 7. Cross-Country Chase

- 8. Lena’s Plea

- 9. The Final Stop

- 10. Morris on Trial

- 11. No Happy Endings

- 12. Lena’s New Priorities

- 13. The Limitations of the Desertion System

- 14. Search Our Records

- Close