Frances Taussig guided the Jewish Social Service Association through challenging historical periods, including the Great Depression and World War II, expanding its services to encompass employment assistance, relief, counseling, and refugee relocation.

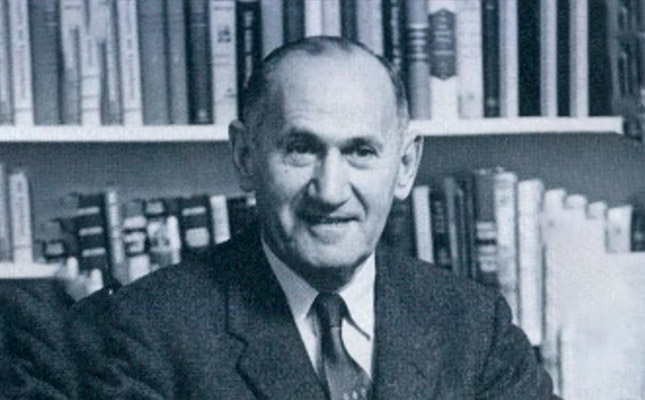

Executive Director, United Hebrew Charities (1919-1926) Jewish Social Service Association (1926-1946) and Jewish Family Service (1946-1949)

Pioneering social work executive Frances Taussig was born in 1883, in Chicago, Illinois. Her father, Samuel, was a candy manufacturer who passed away when she was in her teens, and her mother, Lena (Alexander) Taussig was involved in Jewish community social circles. Little else about her early life or influences is known. A 1904 graduate of the University of Chicago, Taussig worked as the director of the Jewish Social Service Bureau of Chicago and the United Hebrew Society for several years. In 1919, she moved to New York City to become the Executive Director of the United Hebrew Charities (UHC), which was renamed the Jewish Social Service Association (JSSA) in 1926.

Taussig held this position for three decades, navigating the provision of social services to New York City’s most vulnerable during the most turbulent and difficult period in modern world history from the post-WWI years to the Great Depression, period of highly restrictive immigration laws and the unthinkable violence of WWII and the Holocaust. In the years just prior to her 1949 retirement, she oversaw the successful merger of the Jewish Family Welfare Society (a likeminded Brooklyn-based organization) with JSSA, formally becoming Jewish Family Service in 1946.

Under her leadership, the JSSA/JFS expanded from a predominantly relief-based organization to one that provided a broad range of social services to Jewish as well as non-Jewish people in need, including employment assistance, relief, counseling, and refugee relocation, becoming one of the largest and most respected social service bureaus in the United States. Taussig was known for her philosophy of “helping the unfortunate to help themselves,” consistent with the longstanding mission of United Hebrew Charities. Taussig prioritized the development and growth of programs and services that helped individuals achieve productivity and fulfillment, while referring children and families with severe mental illness to the Jewish Board of Guardians for intensive psychotherapy.

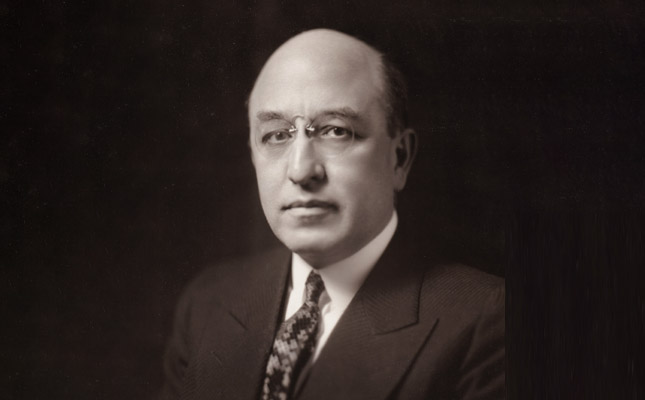

The JSSA approach was distinct from the JBG’s psychoanalytic focus, and there seemed to have been some tension between Taussig and Jewish Board of Guardians Executive Director John Slawson, who in a 1981 interview noted that “Taussig did not ideologically agree with this kind of specialization.” Like her Jewish Board of Guardians counterparts, however, Taussig believed that a reframing of the issues facing those who needed services was essential. Addressing Depression-era homelessness, for example, the JSSA program was ahead of its time in its approach to homelessness as a symptom which could be treated rather than being a condition in and of itself.

The War Years

Officially, Taussig’s story was one of a skilled social work executive adept at managing both broad and detailed aspects of social service. This was the narrative offered by colleagues, newspapers, her own public speaking and writing, and the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services institutional history, 100 Years of Caring (1994). However, a deeper examination of the extensive archival collections related to her suggests a lesser-known aspect of Taussig’s work. These documents suggest that, particularly during the period from 1935 to 1943, Taussig and the JSSA quietly played a crucial role in supporting Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe and in resettling refugees – including unaccompanied children – who arrived through official as well as unofficial channels.

Amid rising antisemitism and a persistently anti-immigrant political environment at home in the US, Taussig worked in close collaboration and alignment with the National Refugee Service (later the National Coordinating Committee), and its director William Haber, as well as the Joint Distribution Committee and other Jewish refugee aid groups, to coordinate a wide range of services for Jewish refugees who had left as well as those desperately seeking to leave Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe. A number of committees were formed to address these urgencies accordingly.

The German Department, as described in a February 1939 document entitled Function and Problems of the German Department of the JSSA, offered “case work service to families and unattached men living in Manhattan, The Bronx, Queens and Long Island, who have immigrated from Germany, Austria, or any of the newly annexed parts of Czechoslovakia following Nazi domination.” The primary goal for this program was to find work or provide relief until work was found, but also to create space for clients to share their problems with the worker overseeing their case. “Problems presented by the families applying for assistance are similar in kind to those of any family finding itself confronted with insecurity and dependency, but are intensified in degree by the arbitrary nature of the circumstances creating this dependency and enforced flight from the homeland.”

JSSA’s Committee on Mentally Sick Refugees, also chaired by Taussig, developed a network of consulting psychiatrists in the area as well as facilities, including Westport Sanitarium and Mount Sinai Hospital, that would be willing to take referred patients who were suffering from significant mental illness and trauma.

The Committees for Displaced Foreign Jewish Social Workers, meanwhile, were a number of collaborating aid groups comprised of social workers “seeking to be helpful to foreign Jewish social workers who are in the United States or contemplating immigration.” Members assisted German and other displaced Jewish social workers in finding placements, offering orientation, and securing fellowships or school admissions to help integrate them into the American social work field. The committee noted that they believed an incorporation of German social workers’ perspectives in the American field would be an added benefit.

Though Taussig and other members of these committees appeared to take great care in the words they used, they hinted at the possibility that the Jewish Social Service Association in fact devoted substantial time, energy, and funding, to the joint objectives of the safe passage, resettlement and social support and integration of Jewish refugees from Germany and Nazi-occupied territory. Dozens of letters, memos and reports in YIVO’s National Refugee Service collection demonstrate the ways she skillfully and thoughtfully directed JSSA to operationalize the crisis mobilization plans and coordination around a number of interventions, with an attention to detail for specific cases as well as the big picture of an unprecedented Jewish refugee crisis.

Frances Taussig’s Legacy

Taussig was nationally recognized for her leadership and expertise, and served as president of the National Conference of Jewish Social Work from 1922-1923 and of the American Association of Social Workers from 1930-1932, and chaired the White House Conference on Child Health and Protection’s Subcommittee on Home Care in 1930. At her retirement in 1949, the Jewish Family Service Board of Trustees celebrated her impact on the agency and the wider field: “When she came, she set herself a goal: to develop the best possible standards of practice. Guiding the Association to deepen its value, concentrating on its essential work rather than spreading its energies, she has been able to develop a staff whose objective is to bring about the most resultful treatment of each client. In the face of financial pressures, this course has required courage, firmness, patience, and high intelligence.”

She seems to have ceased her social service work at this time. It is impossible not to imagine that the work of the war years left a deep and lasting mark for her. Records suggest she may have married a man named John Costas in 1959. She lived to the age of 98, passing away in 1981, the same year as several fellow architects of care explored in this project.

Frances Taussig’s story suggests that there is actually much still to uncover about the critical contributions carried out by the Jewish Social Service Association, the Jewish Board of Guardians, and other Jewish charities during the midcentury pre-war and Holocaust period, and the dual role they often played in providing high-quality social services and secretly working to aid Jewish refugees during a perilous time. The archival records available today suggest a more profound involvement in refugee resettlement than has been widely documented. They present an opportunity to revisit and expand our collective knowledge about the ways in which American Jewish organizations bravely and surreptitiously navigated complex political and social landscapes to fight for the survival and protection of European Jewry during one of history’s darkest periods.