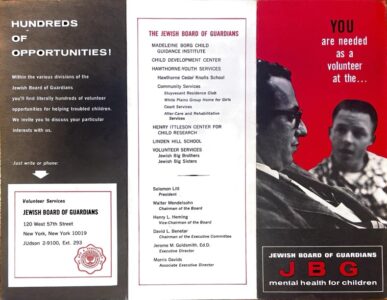

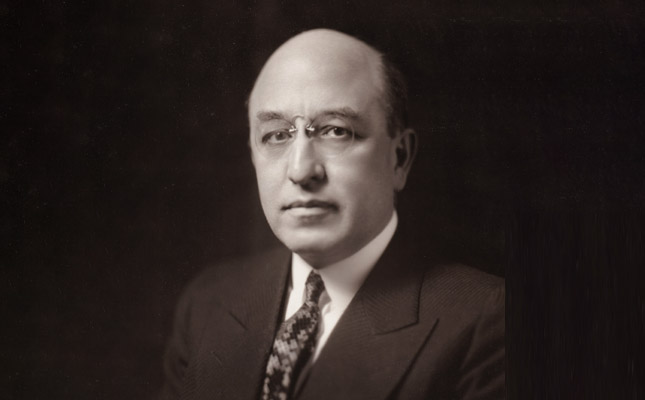

Dr. Jerome M. Goldsmith (“Jay”) transformed mental health services in New York State through his visionary leadership of the Jewish Board of Guardians, subsequently orchestrating the landmark 1978 merger with Jewish Family Service to create the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, Inc. and developing innovative funding models that enabled the organization to become one of the largest mental health and social services agencies in the state and the country.

Director, Hawthorne Cedar Knolls (1951-1965) Executive Vice-President, Jewish Board of Guardians, (1965-1978) Executive Director, Family and Children’s Services (1978-1991)

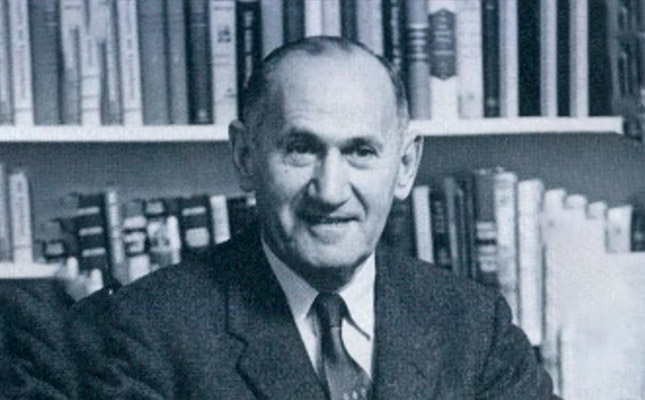

Dr. Jerome M. Goldsmith, MSW, EdD, was a visionary in the field of child and family mental health services. Throughout his nearly four-decade career (1951-1991) in progressive leadership roles at the Jewish Board of Guardians and later the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, Goldsmith consistently demonstrated uncanny foresight, an open mind, genuine love for people, and a creative, collaborative approach to navigating systemic change.

Goldsmith’s tenure with the agency began in 1951 when he was appointed Director of the Jewish Board of Guardian’s Hawthorne Cedar Knolls School, its flagship residential treatment program for troubled youth. He rose to Executive Vice President of the Jewish Board of Guardians in 1965, and for the next decade successfully led the agency during a transformative period in American society marked by the civil rights movement, social welfare expansion, and fundamental shifts in mental health treatment approaches. His work during this time was particularly notable for its anticipation of the long-term impact that Medicaid would have on the provision of healthcare in America.

One of his most significant assignments came with overseeing the 1978 merger of Jewish Family Service into The Jewish Board of Guardians, resulting in the newly named agency — The Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, Inc. Goldsmith led the organization for another 13 years, developing it into one of the nation’s largest social service and mental health agencies.

Goldsmith’s story is a bridge from The Jewish Board’s mid-century psychoanalytic clinical model – and its focus on services primarily within Jewish community – to its recent history and modern identity as an agency providing care to all New Yorkers. While many mid-century mental health and social service agencies struggled with the pressures of Medicaid and social and economic change—often forced to choose between financial viability and service quality—Goldsmith skillfully and compassionately steered the organization through this challenging landscape. In so doing, he played a central role in securing the agency’s future and establishing its capacity to meet the evolving needs of New Yorkers that continues to this day.

Early Life and Influences

Born in 1917 and raised in New York City, Jay Goldsmith’s early life was shaped by personal hardship. At age eight, he experienced the death of his older brother, a traumatic event from which his mother never recovered, herself becoming sick and passing away a short time after. His father was not present. Raised by his grandmother and other members of his extended family, who had very limited means but were committed to providing him with love and connection, his childhood was marked by abject poverty, with frequent moves every few months due to financial instability – but he also recognized that having an alternative to the foster system was an opportunity others like him were not as lucky to have had. These experiences would greatly inform his later work in social services, and his compassion for struggling children and families; as leader of The Jewish Board, he would go on to successfully advocate for more robust mental health care services for children in the foster care system.

Despite the adversity of his upbringing, he obtained his Bachelor of Arts from City College in 1937 at the age of 20. Following graduation, he briefly considered a teaching career, which ended quickly: one of his first days on the job, he decided to jump on the desk to get the attention of his unruly class; at that very moment, his supervisor walked into the classroom. He hastily climbed down from the desk, stepped into a garbage can, and fell over. After this hiccup, he decided to commit to becoming a social worker, obtained his MSW and soon began his career working in Jewish social services in Dayton, Ohio. (Although teaching didn’t work out for Goldsmith, he did eventually earn a Doctorate in Education.)

During World War II, Goldsmith was drafted and served in the Army Air Force, advancing from basic training to Officers Candidate School as a navigator. He was among the survivors of the US Army Transport Dorchester, which was destroyed by a German torpedo in 1943. Four interdenominational chaplains onboard tragically died, along with 672 others, while helping servicemembers by giving up their own life jackets. This was another formative moment for Goldsmith.

After the war, Goldsmith continued his work in social services and relocated to Baltimore, where he worked for a Jewish agency for several years and began to make a name for himself in the field as an empathic, strategic, and bright emerging leader.

Beginnings at the Jewish Board of Guardians

In 1951, Goldsmith became Director of Hawthorne Cedar Knolls School, then home to 300 children. He was selected by the organization’s trustees over competing applicants who had more experience because of his demonstrated openness to innovate, empathy, and unique understanding of public policy issues facing families. Like many of his Jewish Board of Guardians predecessors, Goldsmith maintained that troubled children needed help rather than punishment, and this view guided his approach to child mental health services in a way that was largely consistent with the agency’s existing mission and vision.

Goldsmith implemented several transformative initiatives at Hawthorne. He established formal medical care services by recruiting prominent Westchester physicians, dentists, and psychiatrists to donate their time, creating a foundation for integrated healthcare within the institution. He simultaneously worked to develop strong community relations and encouraged staff participation in local organizations such as the Lions Club and Rotary Club. Under his leadership, the facility cultivated a more family-like atmosphere, encouraging meaningful relationships between staff and residents. These qualities enabled a higher standard of care to be provided, while also contributing to a familiar and less institutional feeling environment.

Goldsmith maintained a long-term interest in children’s residential care, partly as a result of his early years at Hawthorne. He later advocated for funding and standards of care, and one of his biggest victories was securing the conversion of over 700 residential treatment beds in the foster care system to a new program category called “residential treatment facilities” (RTFs) licensed by the New York State Office of Mental Health and funded by Medicaid.

Navigating Change: Medicaid and the 1978 Merger

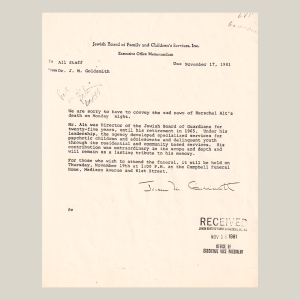

The 1950s and 1960s marked a fundamental shift in child welfare as government funding and oversight began replacing the traditional model of philanthropically funded religiously affiliated institutions. Previously, religious matching statutes directed children to agencies sharing their faith, creating home-like environments that mirrored their cultural backgrounds. This system evolved significantly as the government assumed a more active role. The introduction of Medicaid in 1965 represented a pivotal moment in social service funding, coinciding with Goldsmith’s promotion to Executive Director of the Jewish Board of Guardians, succeeding Herschel Alt’s 25-year tenure.

Goldsmith quickly grasped how this new system would transform residential and mental health care financing. Recognizing that increased government involvement would lead to more regulated services, he strategically built relationships with stakeholders across private and public sectors to position the agency to leverage available resources. As Michael Friedman, Goldsmith’s longtime deputy and Director of Operations, noted in a 2024 oral history interview (link), “the understanding of Medicaid is something that Jay unlike, I think, almost anyone else in the child welfare system had.” Like his predecessors at the United Hebrew Charities a hundred years prior, he understood that individual agencies working in isolation could not effectively impact the broader system of care. Instead, he focused on creating coalitions, bringing together child welfare agencies, mental health providers, and other stakeholders to engage in meaningful dialogue and advocacy.

Goldsmith played an instrumental role in the 1978 merger between Jewish Family Services (which focused on non-residential, family and systems-oriented care) and the Jewish Board of Guardians (which emphasized residential programs with psychodynamic, individual approaches). This union—the natural culmination of his leadership amid broader social and economic changes—brought together complementary clinical methodologies from two complex organizations. His success stemmed from an intellectual openness that rejected adherence to any single treatment philosophy, enabling him to navigate the delicate balancing required to maximize community impact. Following this achievement, Goldsmith became the first Executive Director of the newly formed Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services. In this role, he continued to find ways to partner, innovate, and leverage resources to expand care to more people who needed it, including helping to develop services for severely intellectually and developmentally disabled children.

While the Jewish Board of Guardians had established public funding through its residential programs, Jewish Family Service relied primarily on the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies’ $4 million annual support. Goldsmith recognized that under New York State’s matching program, this philanthropic funding could secure equivalent state funds. He pioneered an innovative arrangement with New York City, using Jewish philanthropic donations as matching funds for state programs, which enabled new services in underserved communities lacking financial resources. This groundbreaking approach to blending private and public funding created a model for leveraging traditional Jewish philanthropy to serve broader community needs.

During the landmark Wilder v. Bernstein case (1973-1986), Goldsmith deftly led the agency as a defendant against a class action challenging religious matching and public funding of sectarian agencies in New York’s foster care system. The court-approved settlement established a “first-come, first-served” placement principle while preserving faith-based agencies’ role and instituting religious freedom protections. This settlement marked a critical transition for constitutional operation of publicly funded faith-based residential treatment services.

Goldsmith was the first non-medical professional to be appointed as Chairman of the New York State’s Hospital Review and Planning Council, where he played a crucial role in the state’s healthcare resource allocation decisions. He became known among trustees for his ability to “pull rabbits out of hats,” securing funding and resources through his extensive network of relationships with state and city officials. He was particularly adept at recognizing when and how to stand firm on an issue and when to push back against political and legislative forces, and when to step aside, adapt, or accept an outcome as final.

Later Career and Legacy

Throughout his career, Goldsmith held several key appointments including chair of the Mental Health Committee of the Community Council of Greater New York and the Governor’s Commission on the State-Local Mental Health System. In 1984, he used his high-level government connections to help the National Association of Social Workers secure expanded insurance reimbursement for clinical social workers. Under Goldsmith’s leadership, The Jewish Board also developed robust professional training programs that attracted talented staff to the agency. He valued intellectual discourse and sought leading experts to guide staff development, establishing in-service training initiatives that became a hallmark of the organization’s commitment to excellence in social services.

Leading the organization during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s, Goldsmith pioneered mental health services for individuals who were HIV positive or diagnosed with AIDS. establishing JBFCS as the first agency in New York City to offer these services free of charge. In a 2024 oral history interview, one person described Jay’s announcement to staff about the role the agency was to play in serving New Yorkers with HIVand AIDS as the most poignant moment in her career. “Jay stood up in front of his Professional Staff, consisting of about 90 people, and spoke in a low somber voice, informing the agency’s leaders, in an unqualifiedly clear manner, that we were going to place Jewish Board staff social workers at the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and see people in our clinics who were struggling HIV and AIDS. He told his staff that he was leaving the room for 10 minutes, and when he returned, he expected that whoever remained in the room would work to support these efforts. He was clear, succinct, and impassioned. No one left that room. This was profound.”

Goldsmith led JBFCS until 1991, remaining actively involved in mental health advocacy throughout retirement with undiminished passion. A “renaissance man,” he had a deep appreciation for art, music, a wonderful sense of humor, and a lifelong commitment to learning. His leadership approach included treating staff as extended family and hosting celebrations at his home, while maintaining openness to differing viewpoints. Goldsmith’s enduring legacy was his unique ability to navigate major transitions in social services while preserving humanitarian values; family and colleagues remember him as someone who “ran into any cause that needed to be served,” who loved all people, and was consequently embraced by the diverse communities with whom he worked.