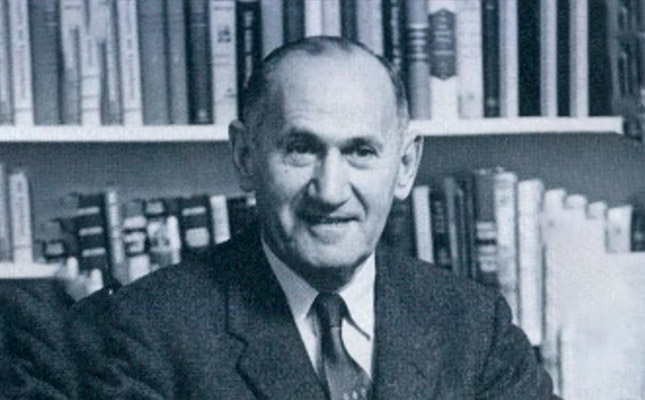

Yonata Feldman was a pioneering psychiatric social worker who, as the first Borough Supervisor at the Bronx Office of the Jewish Board of Guardians, developed innovative approaches to empathically treating children with severe mental illness and mentored multiple generations of clinical social workers.

Bronx Office Supervisor, Jewish Board of Guardians Child Guidance Institute, 1932-1950

Yonata Feldman was born Yente Lowenstein in 1892 in Imperial Russia, and spent most of her childhood in the town of Yur’yev, or Dorpat, which is today the Estonian city of Tartu. Emigrating to the United States on her own at the age of 21 in search of intellectual freedom and professional opportunity, Feldman was ambitious, curious, and very bright. She would go on to become a distinguished figure in the theory and practice of psychiatric social work and was the first supervisor of the Jewish Board of Guardians’ Child Guidance Institute Bronx Office, from 1932-1950.

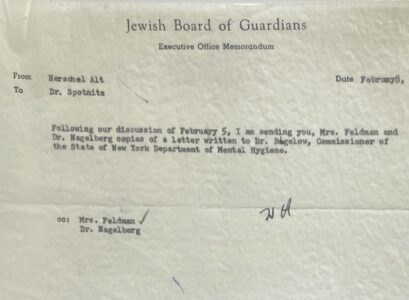

Feldman was highly regarded at the Jewish Board of Guardians for her teaching and mentoring skills, involvement in the Bronx Office Borderline Project, and empathetic approach to casework with parents of children with severe mental illness – as well as for her larger-than-life sense of humor. Though she departed this leadership role in 1950 to become a professor of clinical social work at Smith College, she continued to serve as a consultant to JBG and other local agencies until the late 1970s. In addition to helping countless clients in treatment, Feldman greatly influenced multiple generations of social workers to become more effective and fulfilled in their work. For over fifty years, she championed the recognition of social work as a clinical profession, establishing an enduring legacy as a mentor at the Jewish Board of Guardians and beyond.

Early Life and Emigration

As a primary school student, Feldman displayed a natural talent for teaching, at one time creating a pretend classroom for her peers and landing a job offer from her principal. “In fact, I was paid. She gave me a salary,” Feldman reflected in an undated personal sketch, one of many rich autobiographical documents that comprise the Yonata Feldman Papers at Smith College Special Collections.

Feldman eventually enrolled in the Imperial University of Yur’yev, where she studied history and philology. When World War I began, she left with two cousins in search of work before getting caught in the region’s territorial conflict as Germans troops arrived in 1917. After a harrowing months-long journey, parentless and now a refugee, she secured a trip to the U.S. thanks to the help of a Joint Distribution Committee member who came to her aid in Estonia. The member, who was a Chicago-based judge, learned from Feldman that she had relatives in that city and helped her to secure a visa and emigrate in 1920.

With the support and guidance of her relatives in the Chicago area and local Jewish immigrant aid workers, Feldman enrolled in the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration. As a social work trainee, she leveraged her academic experience from Yur’yev, her natural affinity for teaching, and her multilingual abilities, to build strong relationships with Jewish and non-Jewish immigrant clients with limited English proficiency. This was a transformative experience for Feldman, whose pre-migration life influenced and informed her abilities as a member of American society by equipping her to connect and built trust with socially marginalized families in ways many other skilled social workers could not. Upon completing her master’s degree, Feldman accepted a position as a social worker for the Chicago Jewish Children’s Bureau from 1923-1928, then worked with children with behavioral struggles and severe mental illness under supervision of the Chicago Institute for Juvenile Research.

Tenure at Jewish Board of Guardians

In 1928, Feldman and her husband relocated to New York City, where she became more interested in psychoanalysis and was hired as a caseworker at the Jewish Board of Guardians. She later described her early impressions of the agency as “…a most disorganized place. In fact for a long time I didn’t know what I was supposed to do there, because they had all kinds of divisions — they worked with unmarried mothers, they worked with prisoners. You know we were the probation officers for all the Jewish prisoners. And everybody was in one room.” Yet she also found value in this unorthodox culture: “No other organization could have provided me with the intellectual stimulation that the Jewish Board of Guardians did … The administration encouraged the development of new and interesting ideas.”

Feldman infused her creativity, psychoanalytic approach, and fresh thinking to her work at the Jewish Board of Guardians, earning a promotion in 1932 to Borough Supervisor at the Bronx Office of the Madeleine Borg Child Guidance Institute. She occupied this demanding role for 18 years. Her responsibilities included administrative and budgetary oversight of the satellite clinic, staff training, coordination, and supervision, her own caseload of clients, and maintaining high standards, efficiency, and staff morale — all ingredients that set JBG apart from many other treatment providers at the time.

The Bronx Borderline Project

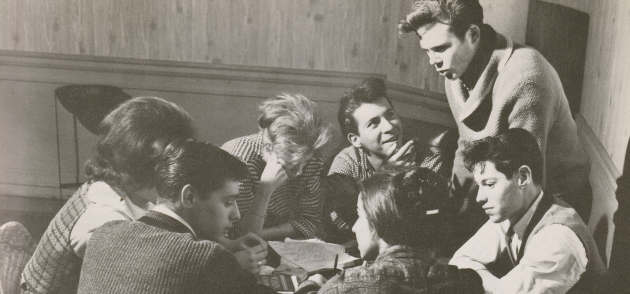

During the mid-1940s, the Jewish Board of Guardians saw a sharp rise in referrals for children suffering from extreme emotional disturbances. Prior to this period, such clients were typically not accepted by JBG in such large numbers. At the Bronx Office, they were frequently classified under the then-used “borderline” diagnosis, though it is likely that many of them were suffering from severe mental illnesses that would not align with the contemporary definition of borderline personality disorder. The “Borderline Project” was developed as a two-year pilot in response to this heightened acuity. However, Feldman welcomed the challenge, “because it met a crying need.” The project introduced group meetings for case presentations and discussions, although Feldman initially found them unproductive due to staff resistance and anxiety over difficult cases. However, over time, the meetings helped workers adopt new approaches to these children, resulting in better outcomes. The project also highlighted the clients’ emotional sensitivity and, in turn, the importance of therapists’ own self-awareness throughout the treatment process.

Through trainings and group facilitation, Feldman encouraged staff to become more aware of their own internal dynamics and helped them work more thoughtfully as a team. She later reflected that her role as supervisor taught her to communicate issues clearly and honestly, which enhanced her training and leadership. Together, these endeavors allowed her to observe how staff interactions – both in relation to each other and with patients – affected not only staff morale but treatment outcomes. This marks the Bronx clinic’s first institutional recognition of the importance of staff dynamics within the broader therapeutic community. In an undated report summarizing the project, she concluded:

“…the Borderline Project has taxed the patience of the Borough Supervisor, and was upsetting to the whole Bronx staff, but what has been emerging in various degrees in single members of the staff is a greater tolerance to emotional onslaught and a better ability to accept frustration, both essentials for doing psychotherapy with seriously disturbed people.”

The increased tolerance and resilience amongst clinical staff improved the organization’s ability to serve its complex patient population, making this not only an important administrative intervention but a clinical one as well.

Later Career

In 1950, Feldman accepted a faculty position at Smith College’s School of Social Work. For many years she continued to consult with the Jewish Board of Guardians, dividing her time between Northampton, MA, and New York. The lessons she had learned about staff dynamics and the importance of quality supervision in the development of effective treatment programs served her well as a professor and mentor to subsequent generations of social workers.

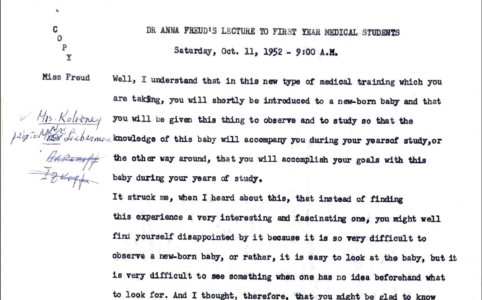

Feldman also authored several articles and books, much of which were inspired by her work and learning at the Bronx Office, that documented case studies with the parents of emotionally disturbed children. In her 1958 article A Casework Approach Toward Understanding Parents of Emotionally Disturbed Children, she emphasized the importance of engaging families through a series of thought-provoking questions that she believed clinicians should also ask of themselves: “Can parents really change their fundamental attitude toward their children unless we fully understand not only what they do and what they say, but also who they are? Can children, even with the most skilled direct therapy, gain enough strength to counteract subtle, yet powerful parental attitudes — attitudes of which the parents themselves are not aware?”

Through this series, Feldman articulated that a key challenge in child therapy involves exploring parents’ unconscious motivations in contributing to their child’s illness. This process “requires the person’s acceptance of a problem within himself and a willingness to participate in a process — something which the parents in child guidance clinics are apparently unable to face.” Understanding how vital such honest confrontation was to the success of treatment, Feldman balanced this challenging work with openness, curiosity, and deep empathy for the family’s struggles.

Legacy

Yonata Feldman continued to supervise students and young clinicians well into the final decades of her life. Her empathy, humor, and unique ability to listen between the lines made her a cherished teacher and supervisor. In the 1982 anthology Yonata Feldman: Master Teacher and Supervisor in Clinical Social Work, former students and colleagues paid homage to Feldman’s singular contributions to the field, particularly the pivotal role she played in shaping social work theory and practice. She inspired her colleagues, supervisors, and students with her conviction that social workers should be regarded as clinical practitioners. She believed their understanding of unconscious processes and interpersonal dynamics allowed them to pursue deeper therapeutic goals beyond environmental interventions and supportive counseling approaches. In doing so, she likely helped emerging clinicians find greater professional and personal fulfillment in their work, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes. Her legacy as a supervisor, mentor, and cherished colleague is unique within the agency’s history.

Reference List, Bibliography and Research Resources

- Smith College Special Collections Finding Aid – Yonata Feldman Papers