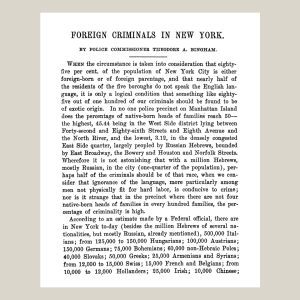

Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany in 1933, riding the wave of antisemitic, white supremacist, and pro-fascist public sentiment he and the Nazi party had been provoking since Germany lost WWI. In response to the clear and growing threat the belligerent regime in Germany posed in the mid-late 1930s, there was a massive wave of Jewish refugees seeking to escape to friendlier lands. This was no easy feat, as those trying to leave would have to contend with restrictive immigration laws in the US and elsewhere in the world, which were first passed in the 1920s and maintained public support as a consequence of the Great Depression. This mass departure was significantly influenced by events such as the Anschluss, the Nazi annexation of Austria, which marked a critical turning point in the intensification of anti-Jewish and anti-intellectual persecution.

Jewish aid organizations across the world, including the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and the Joint Distribution Committee, intensified longstanding efforts to support the emigration of Jews from Germany and Nazi-occupied territories as the decade wore on, and there was a large exodus of Jewish intellectuals, including psychoanalysts, at this time.

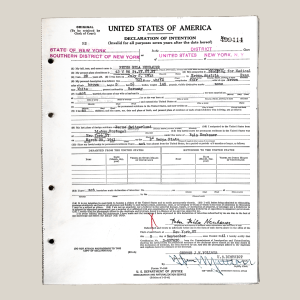

Psychoanalysis was already the dominant approach to psychotherapy in Europe and was gaining popularity in the United States. Most of the leading Jewish Board of Guardians clinicians were themselves Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. They were trained in psychoanalysis, with ties to socialism and progressive education, and had relocated to the US in the early 20th century or during this refugee crisis of the late 1930s. Many of these individuals were able to leave due to their professional networks and resources, which facilitated their escape despite restrictive immigration laws.

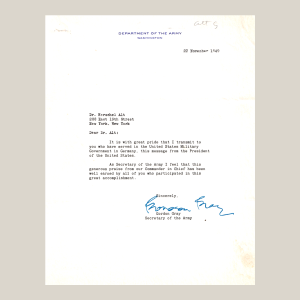

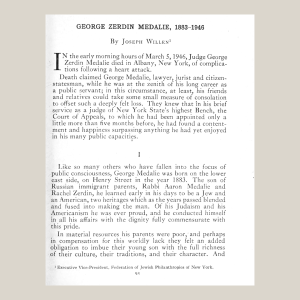

Due to advocacy efforts and the existence of programs facilitating the relocation of skilled Jewish refugees to the US—particularly in fields such as medicine, social work, and psychiatry—this period, which otherwise saw limited Jewish migration, experienced an influx of psychiatrists and mental health professionals. JBG’s émigré clinicians were part of an exiled community deeply rooted in the European intellectual movement that was being targeted by the Nazis. Many of these colleagues made their home in American cities like New York City, Boston, and Chicago, and became affiliated with prominent universities and institutes, including The New School for Social Research, Yale, Columbia, Harvard, and the New York Psychoanalytic Institute. Some returned to their countries of origin after the war. And others did not make it.

Margaret Mahler, a renowned Budapest-born psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who emigrated to New York City in 1938 and served as a consultant to the Jewish Board of Guardians in the 1950s and 1960s, recounted the following in 1988:

I recall the great panic that overtook many Viennese Jewish intellectuals at the time the Nazi troops moved into Austria in March 1938. The Viennese analysts, while naturally sharing in the heightened concern, were less panicked by the political turn than other professionals. In fact, they really behaved in a quite ‘analyzed’ way, banding together in the tradition of the most efficient Freemason groups and undertaking systematic organizational work to see to it that every Jewish analyst was safely relocated.

Mahler’s description does seem to ring true with the work of the Jewish Board of Guardians and the Jewish Social Service Association, which were closely aligned (and would merge to form the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services in 1978). But perhaps because of the organizations’ longstanding mission and Jewish communal roots, they were concerned not only with the safe passage of their Jewish colleagues in psychoanalysis and social work, but with children and families still trapped overseas.

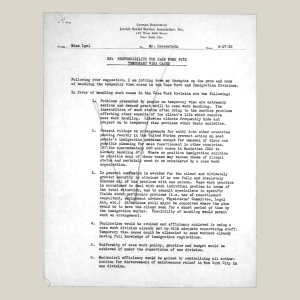

Archival sources suggest that many Jewish Board of Guardians clinicians, including leadership, conducted their work with a specific set of priorities at the front of their minds during this difficult period. From the mid-1930s through the end of the war, was to provide preventive clinical services to as many children in the New York Jewish community as possible, to divert them from the court system, to reduce the rates of juvenile delinquency in a lasting and meaningful way, and to meet the increased need for mental health services they were seeing during this time as a consequence of the war, its physical and emotional toll on families Jewish and non-Jewish alike. “A severely schizophrenic child with its very disturbed parents has on and off always been among the agency caseload,” JBG clinician Yonata Feldman wrote of the treatment of severely mentally children at the Bronx Clinic she supervised. “However, in the past war years, their numbers increased considerably.” Services were expanded to more neighborhoods during the war years, including work with parents and families, and the clinical practice was refined in the effort to improve outcomes. A formal training program for social work was developed, with case conference and treatment structures to support the work of clinicians.

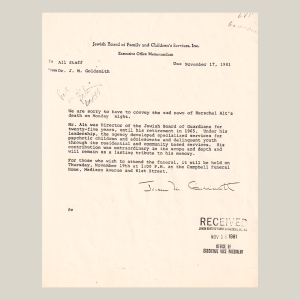

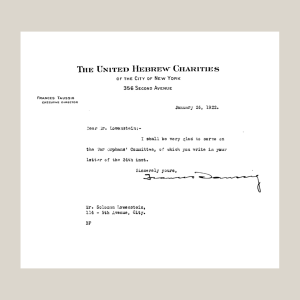

The Holocaust and the war years left an indelible mark on the practice of the joint agencies’ leadership. Some, like JSSA executive director Frances Taussig and JBG president Madeleine Borg, retired soon after the war’s end. JBG executive director John Slawson left in 1943 to work on intergroup relations and investigate the roots of authoritarianism and antisemitism with the American Jewish Committee (AJC), in collaboration with Jewish Frankfurt School social scientists who had developed the field of critical theory, including Max Horkeimer and Theodor Adorno. The result of this collaboration was a five-part Studies in Prejudice, and it utilized case data from private psychoanalytic practices in New York City as well as Jewish Board of Guardian files to investigate connections between early childhood experiences and antisemitic tendencies.