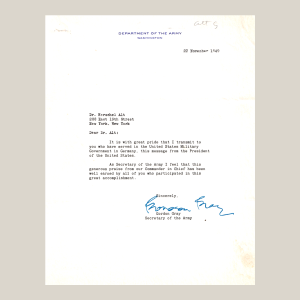

World War II profoundly impacted the practice of psychiatry in the US and Allied countries. The war highlighted to government leaders the need for a healthy population as a critical component of wartime strategy and underscored the psychological impact that combat had on the mental health of soldiers and the civilian population. In 1940, the US Army had only 25 medical officers assigned to psychiatry but would require 2,400 more during the war. It quickly became recognized by the medical establishment as well as the military and the government as an essential service.

Further bolstered by the arrival of European refugee clinicians, psychiatry became a profession with much greater authority, respect, and influence within the medical world. Chief Army psychiatrist William Menninger wrote in 1948 that psychiatry “probably enjoys a wider popular interest at the present time than does any other field of medicine.”

With psychiatry enjoying this enhanced public image in the aftermath of World War II, the United States government significantly expanded its investment in mental health research and treatment. President Truman signed the National Mental Health Act in 1946, which formally established the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 1949. As a result, unprecedented funding became available for researchers and clinicians to advance mental health treatments – with a high degree of autonomy and independence to conduct studies and investigations. This was what historians and mental health leaders alike have called “The Golden Age of Psychiatry.” During this time, states, hospitals, universities, and community providers invested in the expansion of mental health treatment services; scientists first developed psychotropic medications; and clinicians and researchers developed new frameworks for understanding human psychology, including the biological model, cognitive-behavioral model, and social and community psychiatry.

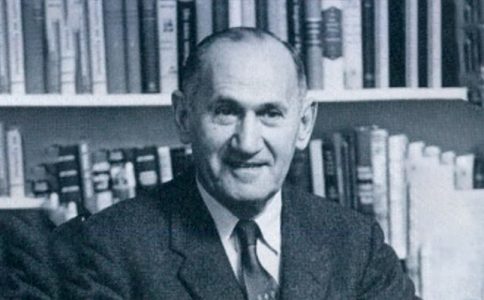

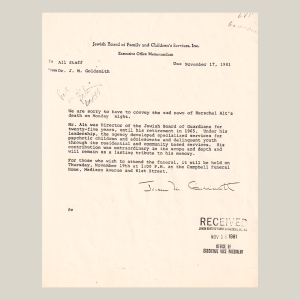

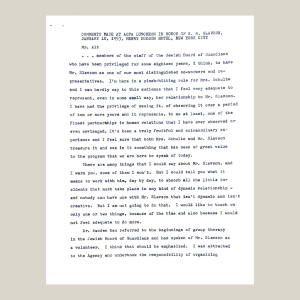

The Jewish Board of Guardians capitalized on new funding and research opportunities made available with the founding of the NIMH. Some of the major areas of research that clinical leaders and Executive Director Herschel Alt (1943-1965) decided to pursue during this “Golden Age” included projects that sought to refine and improve service delivery for those with a range of mental health issues; developing a more evidence-based approach and designing and implementing more effective training for social workers. Though a psychiatrist (and lawyer) by training, Alt self-identified as an administrator above all else. He was adept at identifying where the breakdowns in communication or collaboration were happening in an organizational structure and working to better and fully integrate all of the different aspects of an institution, including treatment, training, and research. He was able to do this, at times merging programs and other times closing them, at child guidance clinics across the country in the 1920s and 1930s before settling at the Jewish Board of Guardians.

What set the JBG apart in the field of child guidance at this point, he and others strongly believed, was the quality of psychotherapy provided by their clinicians, bolstered by a strong treatment team structure and environment that supported creativity. This excellence was often cited as a distinguishing feature of their work in the field, and Alt called it “that JBG magic.” He wanted to standardize it, measure it, and improve it.

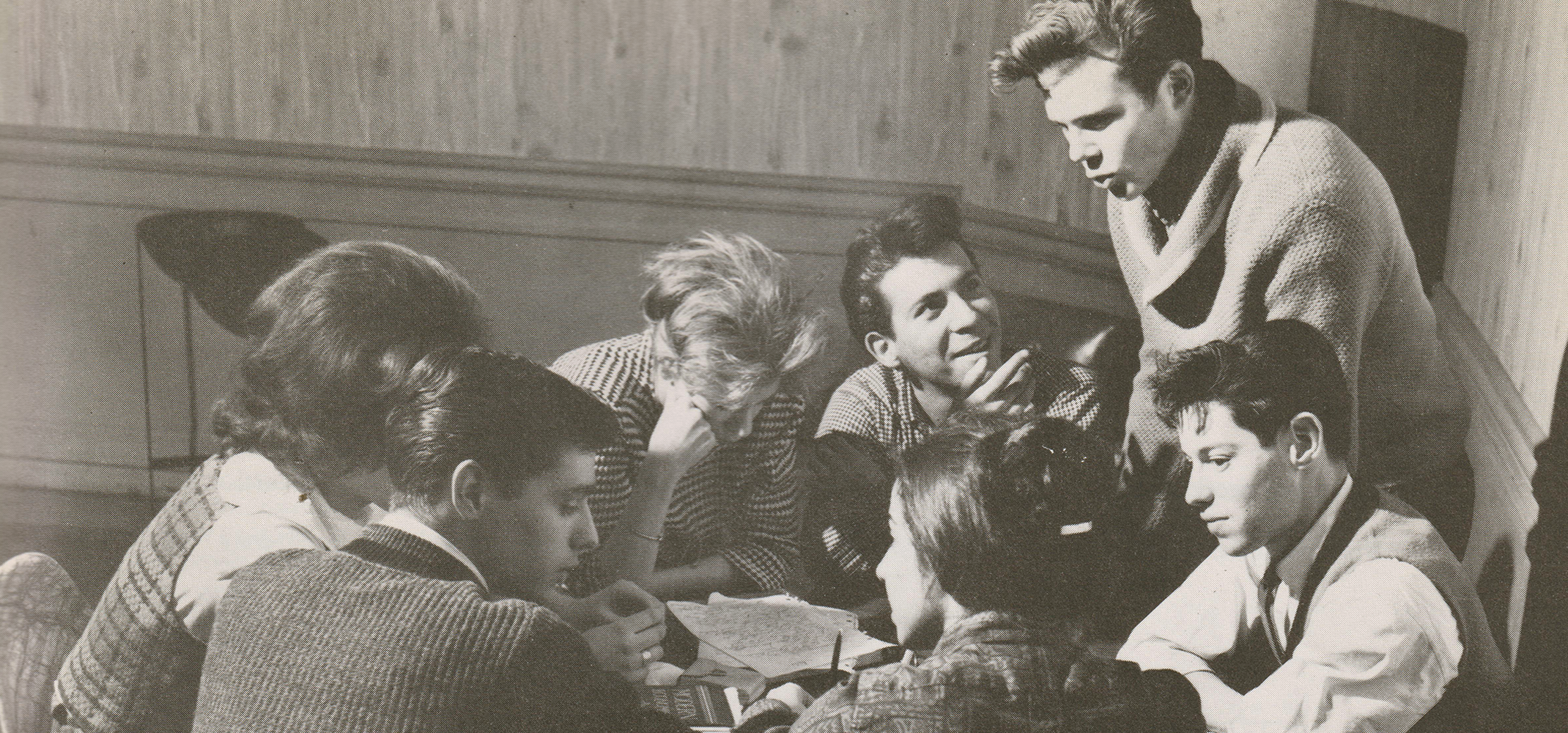

The organization also conducted research in clinics and residential programs across the city to better understand and diagnose mental illnesses and personality disorders, and to provide more specialized treatment, including a continuum of care and step-down services. Under Alt, the agency also worked hard to develop new interventions for those with severe mental illnesses, including children previously deemed “untreatable.”

During this period, many of Jewish Board’s clinicians and researchers – including several who had fled from Europe to the US in the late 1930s and early 1940s, including Peter Blos, Margaret Mahler, and Peter Neubauer, seemed to have an expansive curiosity about human nature, child development, and parental attachment, and the agency’s leadership encouraged staff to pursue their ideas. Psychoanalytic interpretations were no longer limited to the individual therapy sessions, as case workers began to see how interrelated the experiences of parents were with the mental wellbeing of their children. The interpretations that followed did tend to conform with social and economic expectations inherent to capitalist consumerist society at the time, and the source of a child’s “maladjustment” all too often attributed to the coldness or withholding nature of the mother.

A closely related focus of research and clinical work at this time was on expanding the model to family treatment and interventions across the lifespan as well as for a broader range of mental problems and demographics. This included setting up nursery schools, summer camps, daycares, and children’s homes, continuing to refine existing programs, developing new partnerships with schools. It also included attempts to understand how different family structures and characteristics shaped child development, from single mother households to single father households to personalities (authoritarian versus permissive figures) and the occurrence of serious mental illness in parents (especially mothers) In the late 1950s and early 1960s, psychoanalysis had been largely “Americanized” and “Christianized” and these attempts to intervene through the lens of a heteronormative nuclear American family may reflect broader cultural influences of the time, as well as perhaps a desire among recent émigré clinicians to assimilate into American culture.

As the Cold War debate over communism versus capitalism raged on, JBG leaders took a keen interest in the Soviet experience and in how non-Western, particularly communal, societies approached child development. Herschel Alt and others studied the Israeli kibbutz model of child-rearing and co-authored several books on Soviet human development. Their interest appeared to stem from a genuine desire to understand different developmental approaches rather than simply reinforcing popular anti-communist sentiments of the time.

Meanwhile, scientific knowledge had come to be seen as an important tool in the Cold War arsenal, elevating the importance of human subject research and mind control. However, this period was also marked by unethical experiments, revealing that certain safeguards were insufficient to protect human subjects. Research institutions and hospitals across the country participated in problematic studies.

Psychoanalysis would remain the dominant approach until the 1970s, when it began to fall into disfavor, in part because of the costs associated with treatment, the development of multiple antipsychotic and other psychopharmacological interventions, and because of how aspects of its hierarchical structure and normative demands clashed with civil rights era developments and conversations about power, equity, and social justice. With the concurrent introduction of Medicaid, the public funding model in 1965, and the failure of the community mental health movement to become fully implemented and sustained in cities and towns across the country, deinstitutionalization and the financial crisis of the 1970s would bring about a sea change for the Jewish Board and social service agencies across the country.