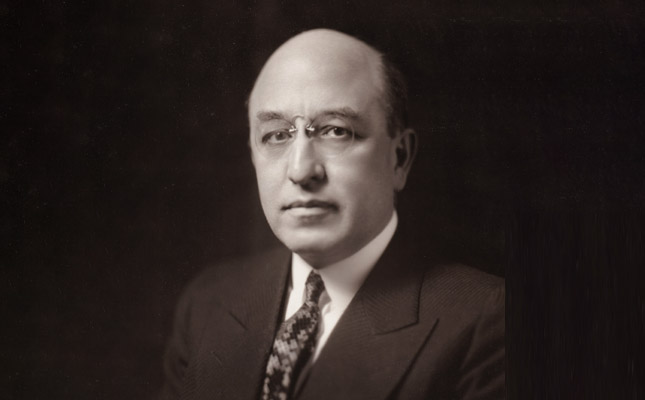

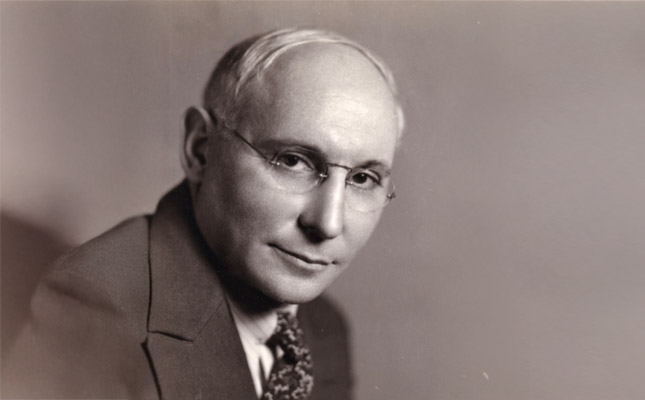

As the first woman to lead the Jewish Board of Guardians, Madeleine Borg was a prominent social welfare advocate who emphasized a holistic and non-criminalizing approach to child guidance and championed the development of therapeutic resources and programs for both children and their families.

President, Jewish Board of Guardians, 1942-1952

Madeleine Beer Borg (1878–1956) was one of the leading figures in the American child guidance and juvenile rights movements of the mid-twentieth century. Perhaps best known for her work as a prominent New York City philanthropist, founder of the Jewish Big Sisters movement, and the first woman to lead the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, Borg also played a pivotal role in the vision and formation of the Jewish Board of Guardians. She served as its president from 1942-1952, and its Child Guidance Institute was named in her honor in 1955.

Born Madeleine Beer to a wealthy New York City family, Borg was passionate from a young age about social causes, strategically leveraging her privilege to fight for improved conditions in some of the city’s poorest immigrant communities. She did not pursue a college degree but completed some coursework in sociology at Columbia University and took a keen interest in the emerging field of social work. She married investment banker Sidney C. Borg in 1898.

Early Career

Borg’s career began as a volunteer worker for the Children’s Court in 1912. That same year she founded the Jewish Big Sisters in response to what she and colleagues perceived as woefully inadequate probation staffing within the juvenile delinquent system. Modeling the organization after the Catholic and Protestant Big Sister groups,1 Borg recruited and expanded a team of women volunteers who worked under the guidance and supervision of professionally trained social workers. These Big Sisters offered both helped their Little Sisters navigate the probation system and offered role modeling to these Jewish girls and adolescents struggling with behavioral problems and acting out.

In 1913, these efforts led to the creation of a rehabilitative home for girls accused of “delinquent” behavior, including petty larceny, “immorality,” and “incorrigibility.” Originally named the Council Home for Jewish Girls, this progressive program became the Cedar Knolls School for Girls when it relocated to the grounds of the Hawthorne School in 1917. These programs come under the umbrella of the Jewish Board of Guardians in 1921.

Advocate for Early Intervention, Training & Collaboration

Madeleine Borg was appointed as president of the Jewish Board of Guardians in 1942, following years of public service in juvenile justice reform and two years after being appointed as the first woman chair of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies in 1939. In part because of her earlier work with Jewish Big Sisters and Cedar Knolls, Borg recognized that early intervention was key.

Many of the girls who came through the programs she had previously led experienced turmoil and instability at home, and she believed that their behavioral challenges could largely be attributed to feelings of emotional insecurity. In her leadership role at the Jewish Board of Guardians, she put great emphasis into the development of therapeutic programs and resources for children and families to divert them from the court system before it was too late. Early intervention was a critical complement to the rehabilitative model of Hawthorne Cedar Knolls and other similar programs, essential to meaningful and lasting reductions in rates of children and adolescents entering the juvenile justice system.

In 1954, the Jewish Board of Guardians opened the Linden Hill School on the Hawthorne campus for boys and girls with severe mental illness and provide more individualized treatment within the signature JBG’s residential program. As chair of the Board of Directors at this time, Borg worked closely with organizational leadership to make the program a reality, and dedicated the building at the ceremony in August 1954 alongside Governor Thomas Dewey. During her tenure, Borg also put significant energy and effort into funding and expanding the reach of the Child Guidance Institute, considered the laboratory where JBG’s therapeutic treatment methods were developed and refined. In 1955, it was renamed after her.

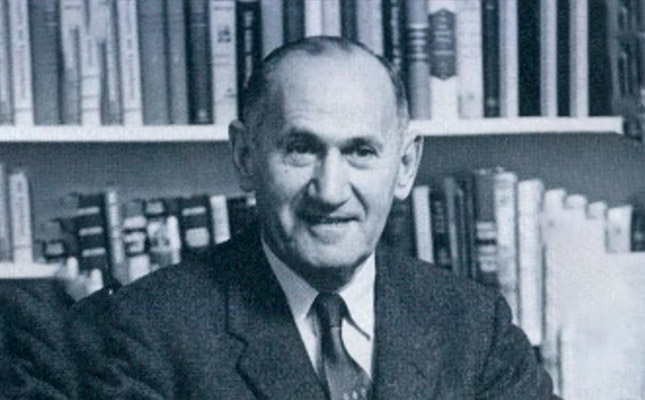

Colleagues including John Slawson remembered her as being skilled in bridging the divide between lay and professional audiences and in building strategic alliances across disciplines. She was known to have understood and respected the primacy of professional training while also ensuring that lay leaders had the authority and autonomy to do their jobs. Her ability to bring different agencies together in coordination and collaboration would prove to be especially important in official activities during World War II, when Borg oversaw the Manhattan office of the Civil Defense Volunteer Organization.

Framing Criminality

Borg possessed an acute appreciation for the ways in which the criminalization of many behaviors seen in troubled children and adolescents was counterproductive, often exacerbating rather than providing relief from these girls’ suffering and instances of acting out. Among her reform efforts, she sought to have the word “delinquent” removed from language in bills addressing children and youth in the courts because of implications about the presumption of “criminality” vis-a-vis the children to which the laws applied, irrespective of whether they had been found guilty of a crime. This was an acknowledgement about the power of language, and one that would foreshadow much more recent discussions and calls to change the words we use when referring to those with mental health problems or who are involved in the modern American criminal justice system.

However, Borg and her closest peers likely lacked critical awareness of how race and racist understandings of criminality, dating back centuries to slavery and the founding of the United States, affected Black children and adolescents. Black scholars (especially sociologists), activists, and civil rights leaders, were certainly engaged in discussions about race, racism, segregation, and the structural differences in exceptions to juvenile justice reform, specifically concerning the treatment of Black children, but this topic does not seem to appear in the archival record in relation to Borg or those with whom she worked. The disturbing increase in racial disparities in the criminal justice system between whites and blacks over the subsequent 75 years serve as a reminder of the insidious racism that has driven policies and definitions of criminality, differentially applied, in New York City and the United States.

A Lens into Gender Roles & Women’s Rights

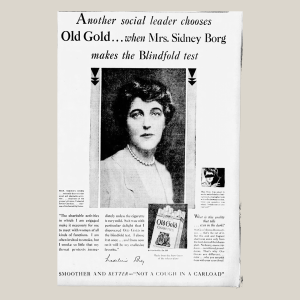

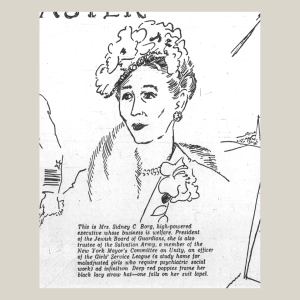

Borg was active in women’s rights more generally, encouraged women to get involved and, as an early member of the Women’s City Club and the League of Women Voters, fought for women’s suffrage. A well-known social figure and symbol of women’s rights at a time of immense social change, Borg was also featured in newspaper ads and style features on multiple occasions and seems to have been a household name not just in New York City but elsewhere in the United States as well.

In the same interview, John Slawson refers to Borg as a woman of great intellect as well as “the most beautiful woman in New York City.” For all her accomplishments, an archival database search using the terms “Mrs. Sidney Borg” turns up many more results than “Madeleine Borg.” So even as she was shattering stereotypes about women, she was part of a culture and place in time. Borg’s story demonstrates the number of competing forces that (mostly wealthy) working women faced in American society, and the tension between domesticity, feminism, and capitalism.

Legacy

Throughout her career, Borg was active in efforts to reframe the way society viewed and responded to certain behaviors.2 She was chair of the 1939 World’s Fair Committee on Social Welfare, was a member of the New York Commission of Old Age Security, and served on a wide array of boards and organizations not mentioned above, including the Salvation Army, the Girls’ Service League, anti-discrimination groups and parole and probation associations.

In 1951, one year before she suddenly passed away, Borg received an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from Columbia University for her outstanding work in juvenile delinquency prevention. She also never stopped advocating for resources and training within the juvenile court system. In 1952, at the 40-year mark of the founding of the Jewish Big Sisters, while in her role as President of JBG, she brought attention to the problem of “simply terrible” salaries for probation officers, which meant that properly qualified individuals would be unlikely to fill these positions. Her efforts to bring change in this arena were sadly cut short with her sudden death that year.

- Over the years Borg would work closely with the leaders of these two groups in advocating for legislation and funding to aid children. ↩︎

- Borg fought to decriminalize prostitution in favor of a mental health and social services approach, and was opposed to Prohibition because she believed its restrictive and punitive framework had a harmful effect on society and Americans’ substance use. She and other women working on social causes during the 1920s had observed that adolescents were actually drinking more, not less, under the 18th Amendment. ↩︎